Dangerous Places: Ethnography at the Global Convergence of Peoples, Labor, and Environmental Movements

— working paper —

Richard Widick

Co-Director, International Institute of Climate Action Theory

Visiting Scholar, Orfalea Center for Global and International Studies

Assistant Project Scientist, Department of Sociology

University of California, Santa Barbara

richard.widick@orfaleacenter.ucsb.edu

This paper was first presented at the Orfalea Center for Global and International Studies on March 11, 2010

This paper has been revised and published as “Dangerous Places: Social Media at eh Convergence of People, Labor and Environmental Movements”, Cyberactivism on the Participatory Web, ed. Martha McCaughey, Routledge [series title: Routledge Studies in New Media and Cyberculture], 2014.

—

Back in the days of Union Carbide, in Bhopal, India, and Chernobyl, a Soviet reactor city then in the state that is now the liberated Ukraine, in a time when the stories of Love Canal and Three Mile Island were still fresh in everyone’s minds, I was studying Environmental Science and learned to call myself an environmentalist. What I knew then is that economic processes are driving the longterm environmental changes I was starting to abhor. So, I added economics to my course of study and learned to call myself an economist, completing the required classes in environmental studies and economic theory with a growing sense of unease about the future. And the most important lesson I ultimately gleaned from these disciplinary adventures came in through the form of the university system and proceeded to run deeper than the content on which I had fixed my senses—it was an epistemological lesson, a general truth about human beings and their collective life: modern societies are like the disciplines themselves, rooted in the philosophical Enlightenment and thus oriented toward the future, institutionally structured for accumulation and expansion with imperial ambitions that are juridically inscribed at the constitutional center of their animating visions by the founding speech (the Constitution; the Declaration; the Federalist Papers, etc.). The Enlightenment philosophies—and especially the Euro-Anglo-American liberal political and social philosophies of Locke, Paine, Smith, Jefferson, and later Mill and the like—have always been and still are driving the interlinked economic processes and environmental transformations that were capturing my attention in those trouble ecological times.

But finally I made Sociology my disciplinary home—a critical base from which to explore the ecological effects of political cultures and their economic development, historically specific in every case. Ideas—for example those of the liberal philosophes mentioned—are collectively forged into the institutions that alone can give a national society the structure it requires to reproduce itself over time, to extend itself in space, and in general to maintain itself as a practical order with a sense of itself as itself—as a nation. And so I learned to call myself a cultural sociologist as well as an environmental theorist, a political economist, and finally a scholar of globalization—for that final term alone has the weight to describe what these past two decades have brought to the world.

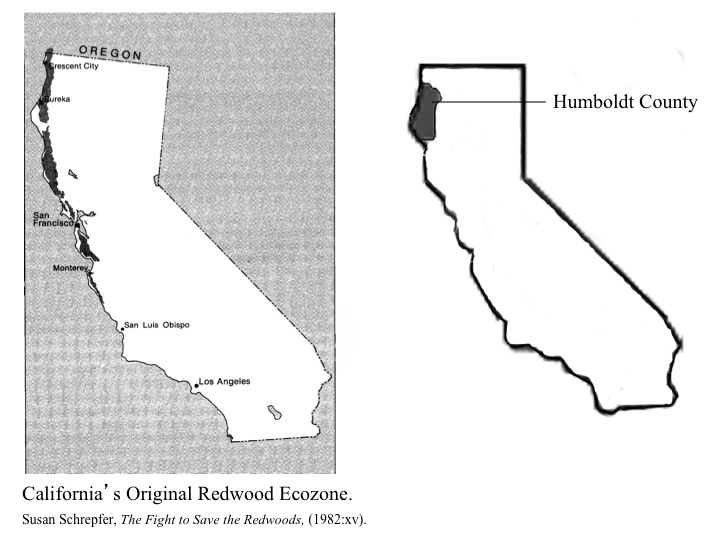

To develop my thoughts in this direction I needed a case study, and the redwood timber wars of northern California were an obvious choice because I had been following them for years already; I knew they were important locally, but also emblematically in the sense that they embodied the historical moment of globalization; also— they were raging through the public sphere the entire time I was in college; they were in my home state; they concerned the most extraordinary ecologies and rivers and mountains; they invited and demanded the most dangerous labor practices; they provoked the most vicious labor struggles; and they assembled all of this conflict on indigenous lands that were not even colonized until the 1850s—thus ensuring that some of the last and most terrifying Indian wars of California would be fought in this place. All told, there is so much history condensed and readily on hand in the region that I took the redwood timber wars as my object and simply asked, what are they? how do they work? and what do they tell us about globalization?

Now the book is out—and I want it to stand as an example of what theoretically informed visual ethnography and social history can achieve when applied in deep, historical, single-case studies of the places being made by the world economic system in this, the epoch of its globalization. In this essay I reflect on the methods I assembled in Trouble in the Forest: California’s Redwood Timber Wars (University of Minnesota Press, 2009) and how what I learned should be broadly applied in Global Studies, Sociology, Political Economic, and History, etc.—in other words, all of the disciplines grappling with globalization and its terrors. I call for the approach outlined here to be applied in comparative work at other, similar places in which ethnographers can not help but encounter the global convergence of Peoples, Labor, and Environmental Movements.

From the start it was difficult to describe the complexity of taking the conflict as the object, not just the powerful forces, not just the struggling opposition, not one group or another, but the timber wars as a whole, as a conflict. I had to devise a way to first experience the conflict directly, myself, and then to write the story that ethnography makes its trade.

Before I go on to describe the case of Humboldt, which I present to you here as an example of how the method can be used, let me reiterate my purpose—I want to generalize the approach and deploy it in comparative work, at the foundations of a new research program focused on the horizon of globalization. There are a lot of places out there where I would deploy graduate students or go myself, if I could, or even dedicate the resources of a research institute, if by chance I found myself at the helm of a globally funded program intent upon engaging and transforming the myriad of struggles now forming up everywhere that globalization touches down, in the places where world economic system expansion externalizes cost on labor and environmental communities. We could, for example, study the Appalachian coal wars; the so-called frack wars over controversial techniques of natural gas extraction from shale rock formations; the Gulf oil wars; the south-western water wars, and so-on. And why not move beyond the US theatre to study the Nigerian Delta Oil wars, the Brazilian rubber wars, and so many others struggles that embody the same overarching forces of globalization and the various, even myriad First Peoples, poor peoples, labor, and environmental resistance movements? The places being made in these conflict zones are comparable to the Humboldt Bay redwood region, and in my view only well-crafted, theoretically informed ethnographic stories are supple and complex enough to articulate what we can learn and need to know about globalization.

Because environmental conflicts tend to be place-based, for obvious reasons, the method I suggest must begin and end with the experience of place. We must encounter the forces of globalization at work in specific locales, the places in which we can directly encounter the various powers and forces at work.

The ethnographer is s/he who, in the words of Clifford Geertz, goes out there and comes back with a story to tell. That is the master trope of ethnography, the inaugural figure of speech under which all of our efforts embark—we are the ones who must make the journey into another world, or sphere, or field of power, and subject ourselves to the linguistic, cultural, and natural forces at work, before reporting back on what we have found, hopefully in well-crafted stories that preserve material from the unique or threatened cultures we encounter and make them available in our home spheres for better understanding of the world large, the other, and perhaps even better orienting present and future politics and action in the interests of promoting a better world.

Those are, each and all, the usually unspoken pretenses of the disciplines on which the ethnographer learns, through necessity, to prey and become parasitical; anthropology, sociology, political science, the physical sciences, biology, chemistry, etc.—the ethnographer must be prepared to enjoin every discourse that participates in the constitution of the object under investigation.

The common project of every modern discipline is the application of science to the individual and/or the collective body, for the creation of knowledge of the object under study, knowledge for improving that object or making it useful, or for making it further amenable to rationalization, whether it be the nation, the town, the body, the factory, the asylum, the school, the organism, the crops… whatever.

The Redwood Timber Wars

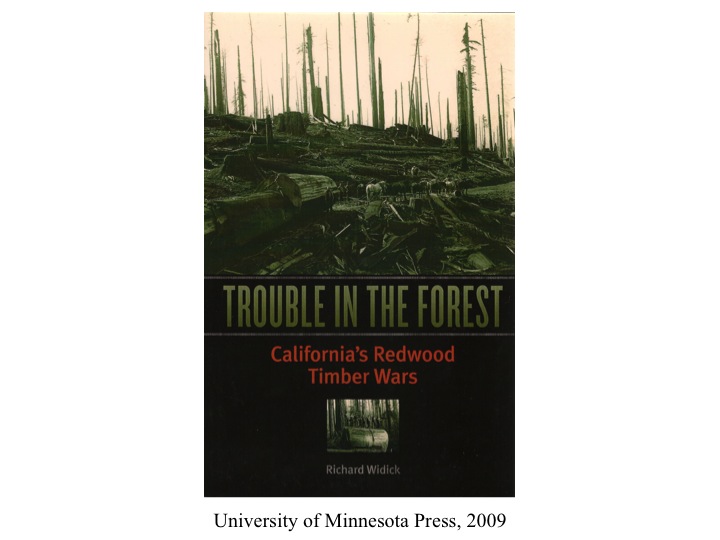

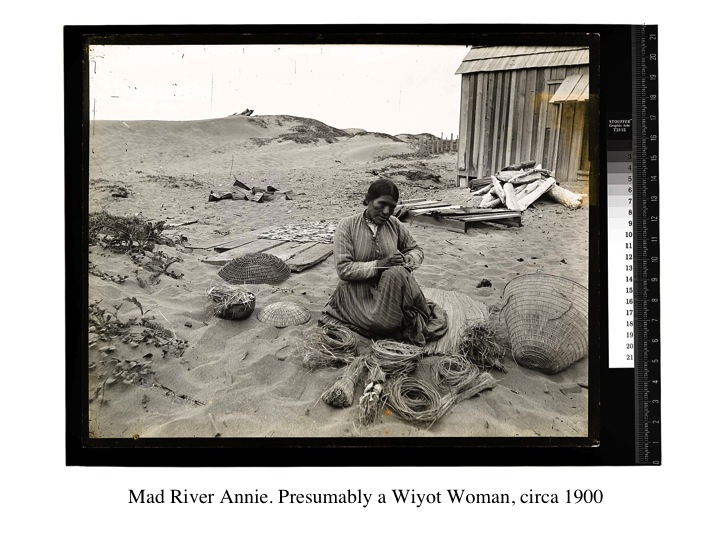

Let me begin by introducing the place of the redwood timber wars by way of an undated photo from the late 19th century, at the end of the colonial era but before the era of chainsaws and tractors, which began in the early 20th century.

This place, as I will explain, is dangerous in part because of the archive of photos from which I took this image, and because of all of the other images and narratives and physical changes that have accumulated here, in this archive—and I’ll try to explain how I came to treat this whole place as an archive, a dangerous archive.

In this photograph we see first of all what was done to most of the region’s primeval forest, and second of all the incipient technologies with which redwood labor accomplished all of this over the next 100 years, a century during which they cut 96% of the redwood forest—96% by 1985.

And what does that fact (they took 96%) suggest came of the indigenous peoples who lived there? The Wiyot people who inhabited the bay were reduced from somewhere between 1500 and 2000 to perhaps 200 between first colonization in 1850 and the massacres of 1860. I will have more to say about this, and show, below.

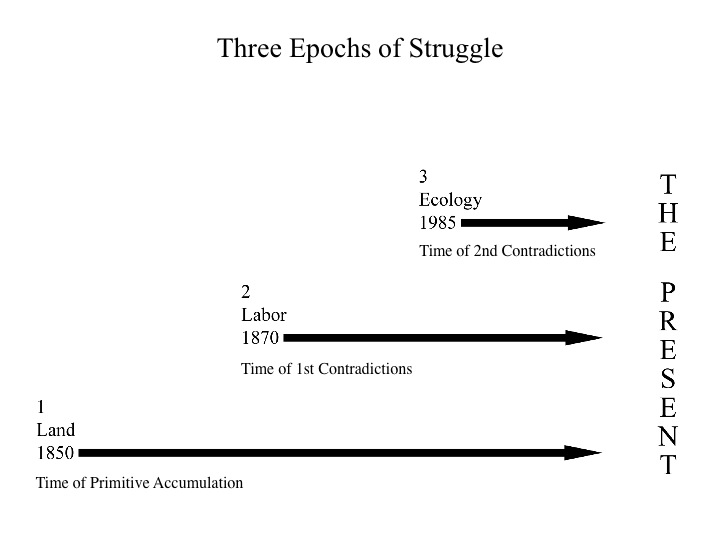

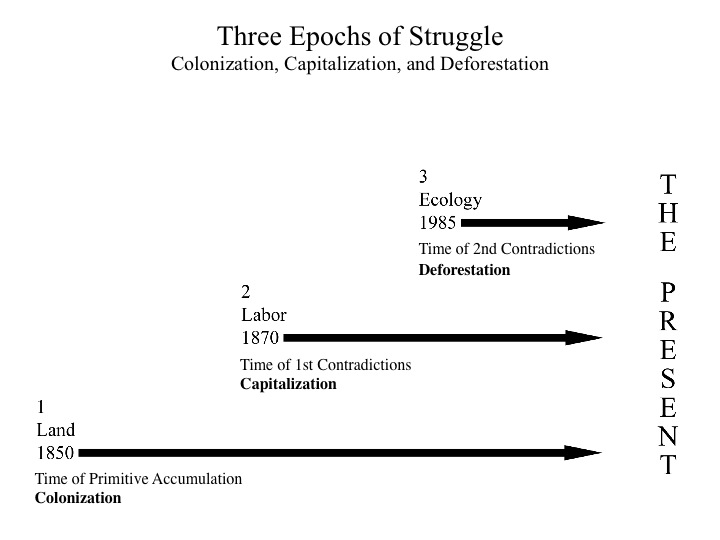

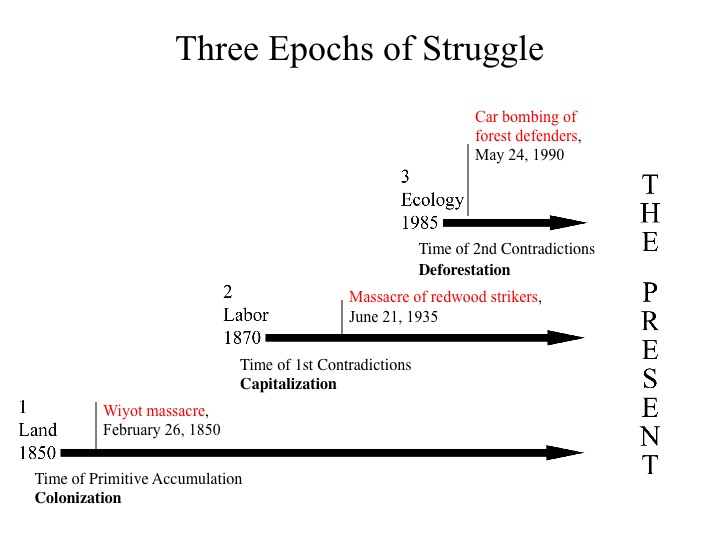

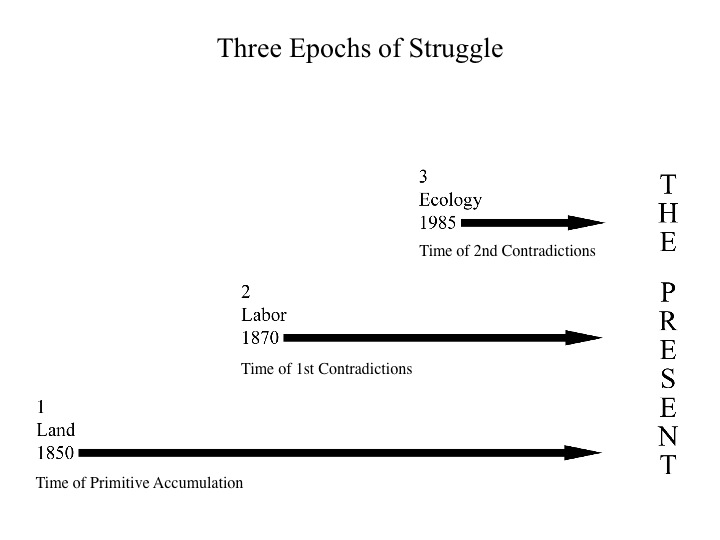

It will help to introduce the history of this place schematically, at first, in order to get oriented: first came the colonial Indian genocide and concentration of the remnants of the tribes on the reservations. Thus went the time of primitive accumulation—accumulation by force, prior to and constitutive of proper capitalist accumulation.

It will help to introduce the history of this place schematically, at first, in order to get oriented: first came the colonial Indian genocide and concentration of the remnants of the tribes on the reservations. Thus went the time of primitive accumulation—accumulation by force, prior to and constitutive of proper capitalist accumulation.

This entailed the privatization of these lands in the legal property system, which readied the land for the coming decades of all out industrial competition in redwood production. Thus went the time of internal contradiction in capital—the so-called first contradiction, according to environmental theory, the time of constantly increasing scales of production and the continuous division of labor and the concentration of ownership and speed-up and relentless substitution of machinery for labor.

The result? Massive accumulation of redwood capital; massive power exercised over labor; and thus massive alienation of redwood labor from its own product, from itself, from the process of work; and ultimately from other workers—real domination!; and finally the push back, labor organization; strikes; the violent repression of the movement; and in the end a compromise formation allowing smooth, rapid, massive escalation of production. Nearly total deforestation is the result. 96% was cut.

In the process—the social and environmental conditions were set fort the redwood timber wars that erupted in 1985. That was the year tht global financial forces moved into Humboldt.

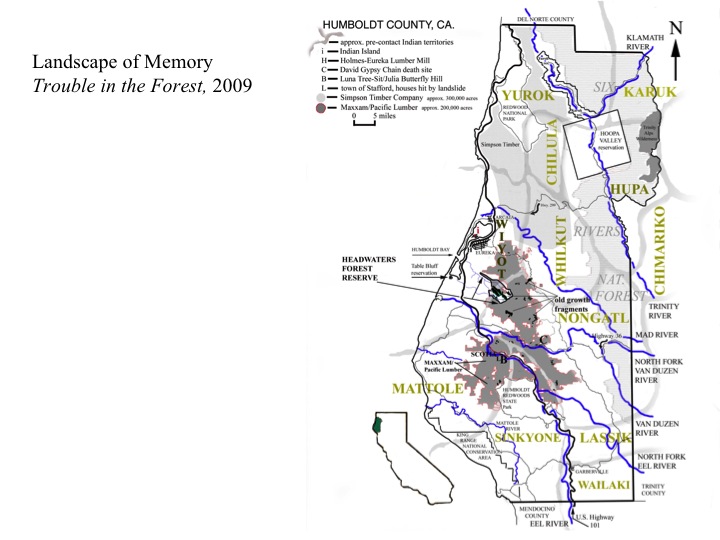

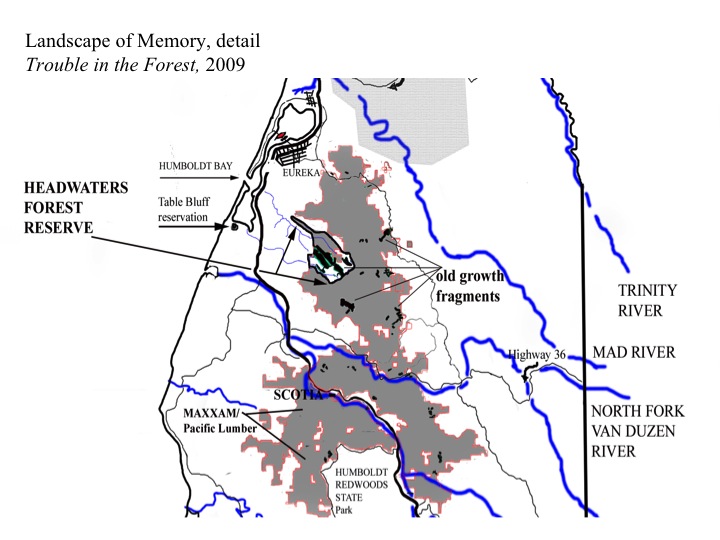

CEO Charles Hurwitz brought the MAXXAM corporation into the redwoods on a wave of deregulated junk bond leverage—buying up the local Pacific Lumber, owner of 200,000 plus acres, including most of the last 1% of uncut and unprotected old growth. And right away he made the public claim that he was going to cut it all. 96% was already gone. 3% was already preserved in parks, and he said to the media that was taking the rest for himself.

The last 1% of ancient trees in Humboldt county are shown here as the tiny black fragments—nestled in among other details of land ownership in the year 2000. They ar all within the grey area indicating the acreage owned by PAcific Lumber/Maxxam. And see the indigenous language territories and reservation.

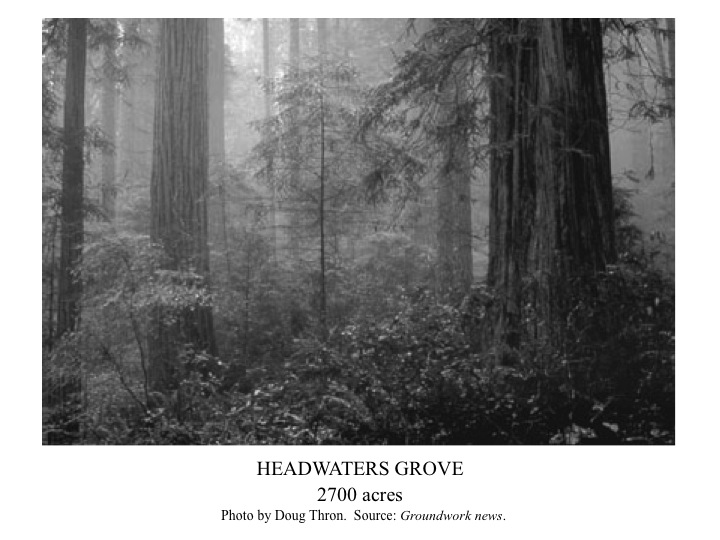

In this detail from the map, Headwaters Forest is more clearly represented; at 2700 acres, it was the largest remaining uncut and unprotected ancient grove at the time.

And in 1985, Hurwitz says he is going to cut it all, a gesture that helps make Headwaters the symbolic center of the incipient network of forest defense movements.

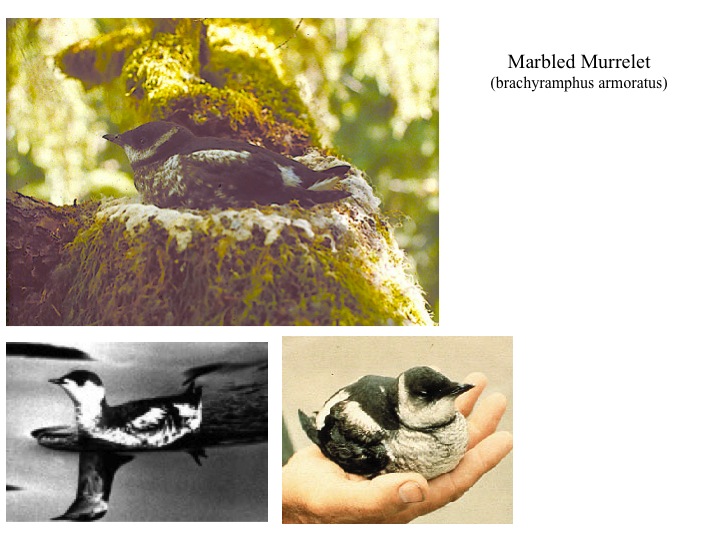

These are two of the endangered species using these forests, the marbled murrelet and the spotted owl. The forest defenders used the endangered species act to fight back. They sued and sued, repetitively, and they conducted a relentless campaign of civil disobedience.

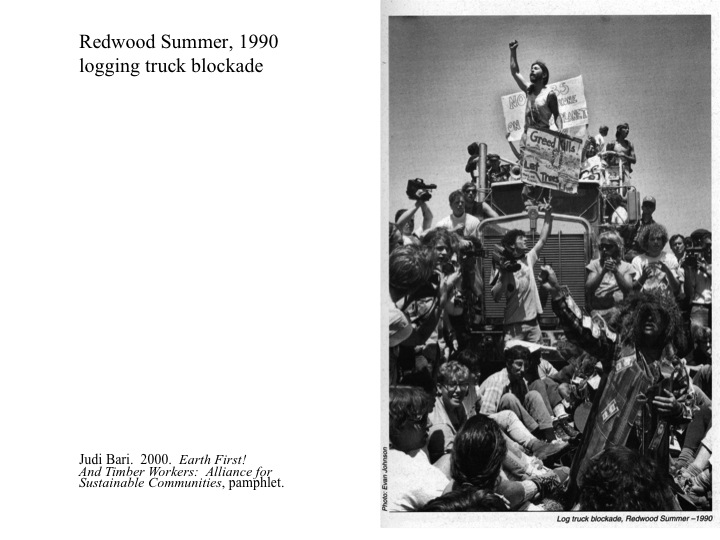

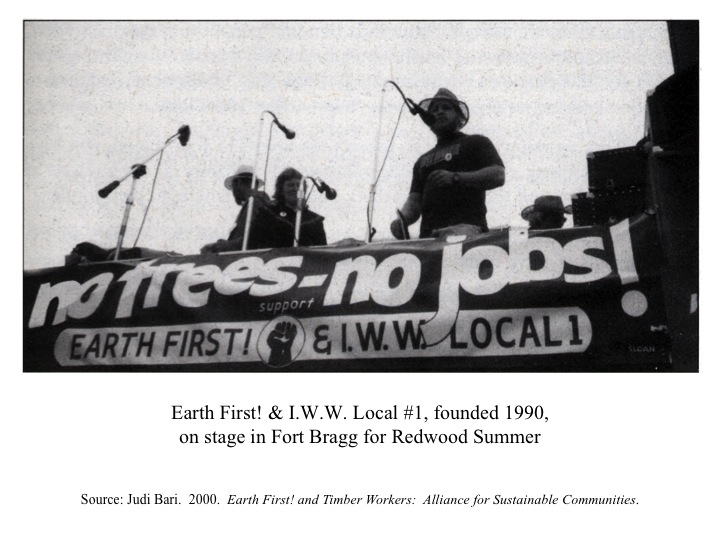

Then they carried out the largest environmental rally to date—Redwood Summer, in 1990—a whole season of direct action civil disobedience modeled on the so-called Mississippi Summer of 1964.

The idea was the same—create an influx of outsiders capable of breaking though the monopoly on established reality exercised by the timber industry—just like the white monopoly held over power in the 1960s south. People came from all over the nation to shut down the logging and defend the ancient redwoods.

The idea was the same—create an influx of outsiders capable of breaking though the monopoly on established reality exercised by the timber industry—just like the white monopoly held over power in the 1960s south. People came from all over the nation to shut down the logging and defend the ancient redwoods.

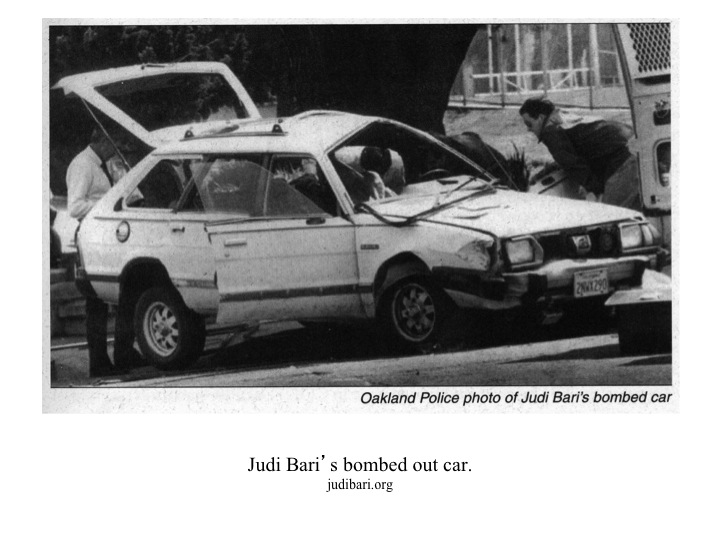

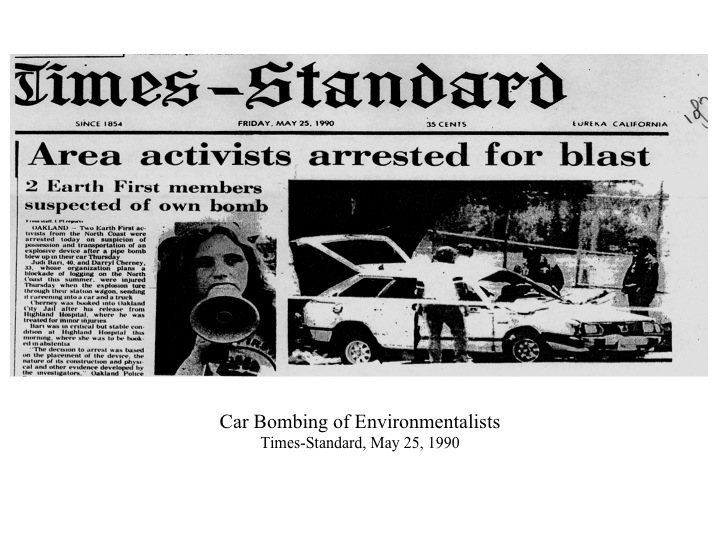

But right before the summer season of protest began, lead organizers Judi Bari and Darryl Cherney were car bombed.

Bari and Cherney were not killed, but the FBI did arrest them for carrying the bomb and associated the movement with terrorism in the public sphere with several press releases and appearances. In the end the FBI never pressed any charges, because there was no evidence. But, by investigating the victims and not doing a wider investigation, the movement was tainted in the media.

Bari and Cherney were not killed, but the FBI did arrest them for carrying the bomb and associated the movement with terrorism in the public sphere with several press releases and appearances. In the end the FBI never pressed any charges, because there was no evidence. But, by investigating the victims and not doing a wider investigation, the movement was tainted in the media.

In the following months there were more logging lawsuits against MAXXAM, and so Hurwitz decided to file a 5th amendment takings lawsuit against the federal government, claiming that the ESA murrelet regulations had taken all of the value of his property at Headwaters Grove.

In 1999, that lawsuit was settled out of court with the so-called Headwaters Deal, in which the combined funds of the federal government and the state of California paid MAXXAM 500 million for the 2700 acres grove—even though Hurwitz had paid only double that for the whole company, which held 200,000 acres, plus the town of Scotia; a giant welding company (later sold for 30 million); an office building in San Francisco (later sold for 50 million); and more.

So the movement saved Headwaters grove, in the end, but not before it had lost something just as important, if not more important, back in 1990. In that year, the Humboldt forest defenders wrote and brought to the people a ballot measure called Forests Forever, which would have made it illegal to cut any tree in California older the 150 years, as well as outlaw clear cutting methods altogether.

It was on the ballot in November, right after the bombing and the following events of Redwood Summer—and it lost by merely 1%—in a media climate/spectacle of the car bombing in which the FBI was investigating the movement for terrorism!

That was a huge victory for Big Timber. And they ultimately got the Headwaters Deal as well; and they got to keep on cutting old growth for another 20 years; and clear cutting the whole time—they still are! And so the end result was that they have been able to accumulate hundereds of millions of more dollars.

Violence against the movement worked. Whoever bombed Bari’s car succeeded in that respect, at least. And they have never been caught.

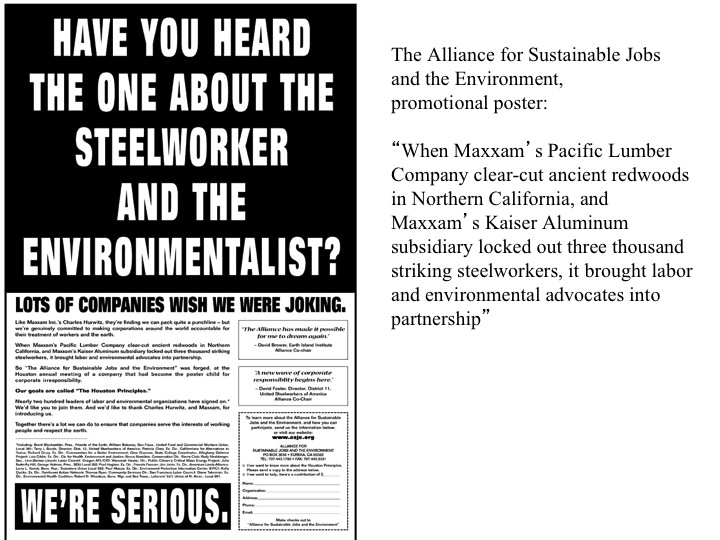

Going back to 1988, we see that MAXXAM had another problem brewing; in 1988 it acquired the Kaiser Aluminum Company in yet another leveraged buyout. Kaiser was global and unionized. And by 1998 the company was locked in a heated contract renegotiation with its United Steel Workers.

When the negotiations broke down, the steel workers went on strike, and then MAXXAM locked them out, and believe it or not, they shipped in laid off timber workers from Humboldt; they sent in lumber men to replace steel workers at their Spokane Washington factory. They even drove them onto the site in ominous looking buses with blacked out windows.

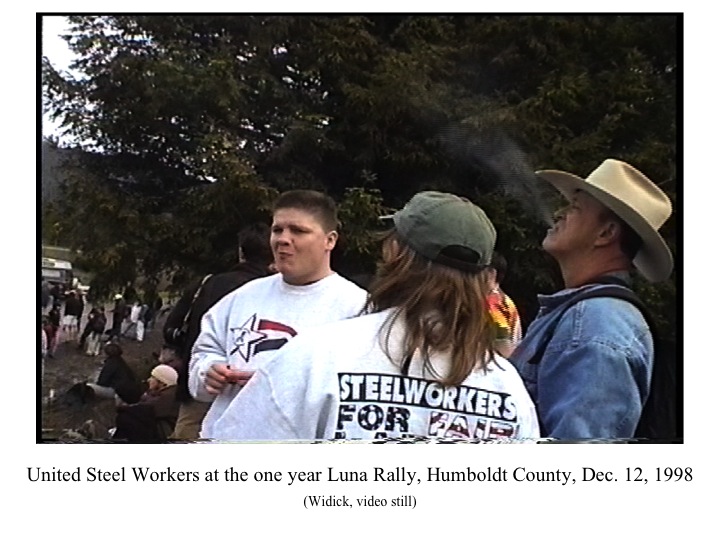

The steel workers promptly headed down to Humboldt and allied themselves with the forest defenders.

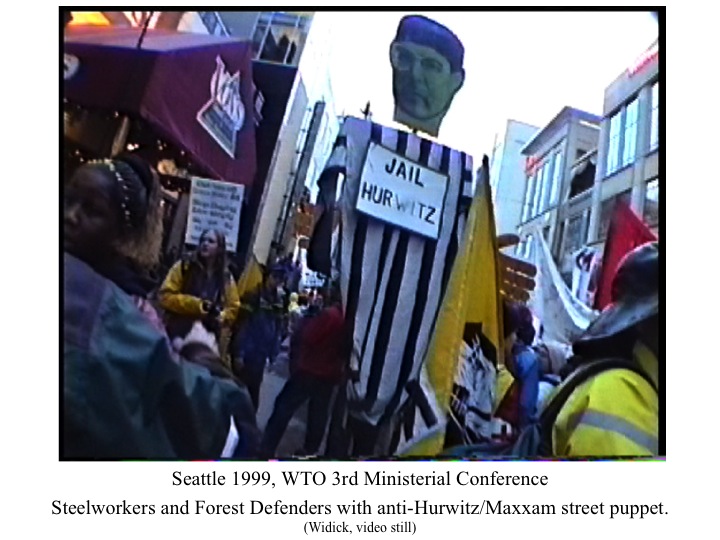

And then in 1999 United Steel Workers from Kaiser and Humboldt forest defenders marched together in Seattle against the WTO. The picture shows an effigy of Hurwitz, and there were steel workers marching at the head of the column (not shown here) with about 50,000 workers and environmentalists behind them.

MAXXAM had made itself into a world historical symbol through which these labor and environmental movements could and did identify and combine. They converged and they fed their convergence into the great convergence that we now call the ballet in Seattle.

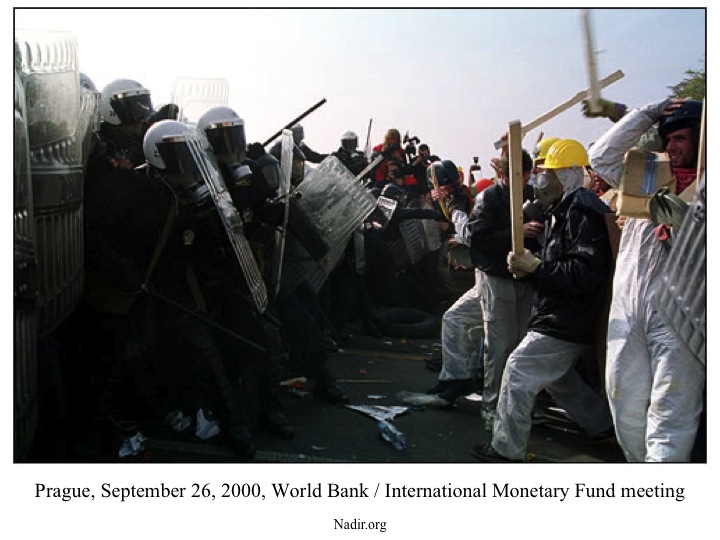

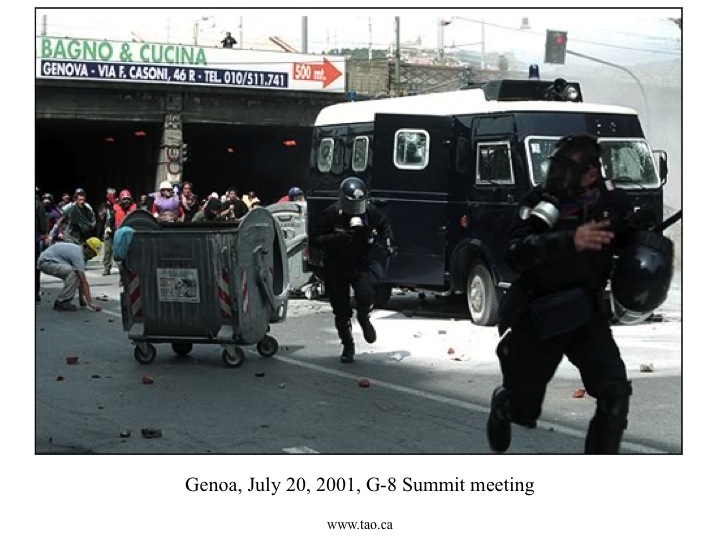

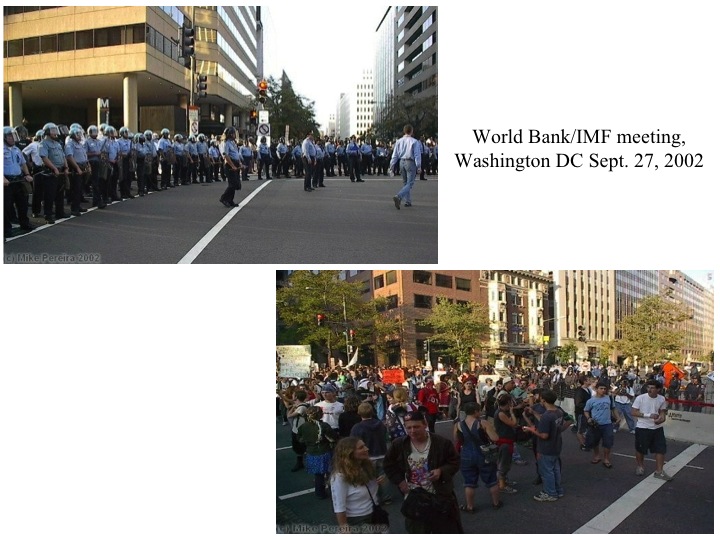

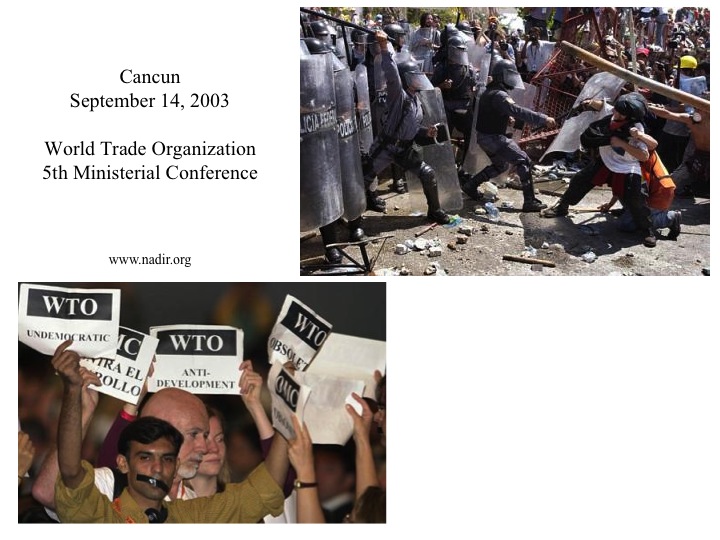

What followed was of course the historic series of similar anti-globalization convergences that helped change both the discourse and the practice of globalization—across the globe, wherever the power brokers tried to assemble, peoples, labor and environmental movements came together.

And it goes on and on, all the way up through Copenhagen 2009 and presumably into the future.

As you know, the FTAA is a dead letter, it’s over. The Dohar Round of WTO talks is perpetually deferred and its goals incomplete. And now the endless war on terrorism, the drone wars in Yemen and Afghanistan, Iraq and Afghan ground wars; Pakistan, Somalia, and everywhere—for a long time opposition to these wars has drawn on the same reservoir of attention. And then came the great economic crisis, the great recession, and the deal seems to be cinched. So much of the movements’ analysis is coming true: namely, expansion, crisis, war—capitalist globalization advances with crisis and war; and civil societies respond. Think for example of the Bolivarian revolution; the rise of Europe; the rise of China.

The Washington Consensus is collapsing; neoliberalism has at the very least been body checked (however briefly). We might even get a Tobin Tax out of this, eventually.

All of these changes, and more, are connected to the internal structures of this emergent global system.

The point is that world economic (culture) system expansion, undergoing the process of globalization, drives the ongoing integration and emergence of global civil society. The market sphere rises and globalizes; so then the public sphere rises and globalizes; capital produces the condition of the social moments; private accumulation leads to public struggles.

And Humboldt is just a single case where this global process implodes in the local.

That is one thing that globalization keeps on teaching us; that it brings the local more dearly into play; that is the lesson for global ethnographers.

We need more case studies like mine in Humboldt to document how globalization is producing places like this—places where companies like MAXXAM express the forces of globalization in specific locales and produce the conditions for converging peoples’, labor, and environmental movements.

There is a report coming out from the UN this summer, it shows how the world’s top 3000 corporations produce so much external environmental cost that paying for them would eat up to 30 to 40 percent of their profits.

In my view, that is a conservative UN-style estimate. Remember, I’m an economist at heart—I shave studied how firms plan their internal pricing—microeconomics, in other words, the theory of the firm. The first rule of thumb is that avoided cost is profit.

And if you added social costs to these environmental costs, well, I bet those 3000 corporations would not even break even. Of course, the problem with that argument is that you have to put a dollar value on what are essentially non-market goods, and that is a matter of preferences, not too scientific—it’s a matter of values, morals, and philosophy. It is culture, in other words, and it raises this question: “how are values actually established and reproduced.” That is a very hard question, and it must be treated historically in every case.

But we can make one very logical and qualitative statement with complete certainty: profits have to be taken from somewhere, and/or from someone, if they are going to accumulate privately as individual profit.

Capital is privatized social wealth. That is what the struggles are all about.

The companies are engines driving the production of dangerous places as they privatize social and natural wealth. But really they are embodying and expressing the forces of globalization—and in that they are the avant guarde of the world system, they are the new dominant tendency.

Going back to the case of Humboldt and our three epochs of struggle…

We need to add colonization, capitalization, and deforestation to this story of converging social movements. It is the story that makes this place dangerous. And who can tell that story? The ethnographer who takes the whole place as the object of investigation. The place itself has been made into an archive. It is the institutions, texts, and physical geography of this place that are the archive that records and reveals the common conditions and common cause of the various movements. This common cause, admittedly, is a complex cause; but it is one that can be studied and explained, and that is what I did in my book.

The cause, stated simply, is colonization by the culture system of modern capitalism, but the system itself must be dialectically conceived as a conflict in order to stay true to both our experience and the theory.

Before I specify the term system of modern capitalism more concretely, one more remark on the idea of dangerous places will be helpful: Let me make the point in the form of a question. To whom, exactly, are these places dangerous? The ruling classes; the established reality; the dominant order; and so, to the colonizing culture itself; and in Humboldt that means it is dangerous to the timber industry hegemony, to the redwood commodity circuit.

You can see right away the strictly dialectical form of this point: colonizing capital culture produces this archival place, which now constitutes the danger to that very culture.

In this way, the term dangerous calls to mind the second part of Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt’s book Multitude. Remember that their previous book was Empire—referring to the expanding empire of capitalism, otherwise known as globalization; that’s our word again, right, for the inexorable tendency Marx described in 1848; he called it the process that chases the bourgeoisie all over the globe; the all-out competition that melts everything solid into air…

He even said that every river would be dammed and every forest leveled. He even said, watch how it will produce revolutionary advances in communications and transportation technologies (thus presaging McLuhan’s global village, Gidden’s time-space distanciation and dis-embedding, and David Harvey’s time-space compression and what he called the machine of fragmentation; and of course Gidden’s phantasmagorical modernity; and finally Castell’s network society).

The ongoing rise of the Empire of Capital produces all of the miserable classes, the dangerous classes, the classes whose labor power is subjected to force and thereby alienated systematically so that it accumulates as private capital and comes to stand over and oppose those classes with ever greater strength.

Capital produces these conditions of labor movement; and the conditions of the peoples’ movements too; and finally the conditions of the environmental movements. It produces the conditions for these movements, but of course the people still have to make the movements.

We understand the working classes pretty well; everybody who has a boss and works for wages is part of the working class. But the term multitude is a broader category containing all of the productive forces and classes and the suffering classes, the alienated and surplus populations that don’t fit the easy definition of the working class I just gave, but which still become dangerous to capital when and if its members recognize their common cause.

Admittedly this is visionary thinking; hopeful utopian political thought; very philosophical! That’s fine, there is a place for that. And I am taking that step here by talking about Dangerous Places in the same way.

Dangerous places are places that in their very structure as places act as a priori cultural systems for articulating the convergence of peoples’, labor, and environmental movements.

I am using the terms structure and system and articulate very precisely here, because what I did as an ethnographer of the place of the redwood timber wars, was develop a linguistic metaphor to describe what I found—to describe the place that the colonizing culture of capital made. It made this place into a structure—its geography and its history are a grammar and a lexicon for future consciousness and politics.

This is where I bring cultural sociology to bear, and remember—this is what the global ethnographer has got to know; this is the kernel of theory to be taken into the field, to the 3000 places—to be tested and to generate the questions that guide research.

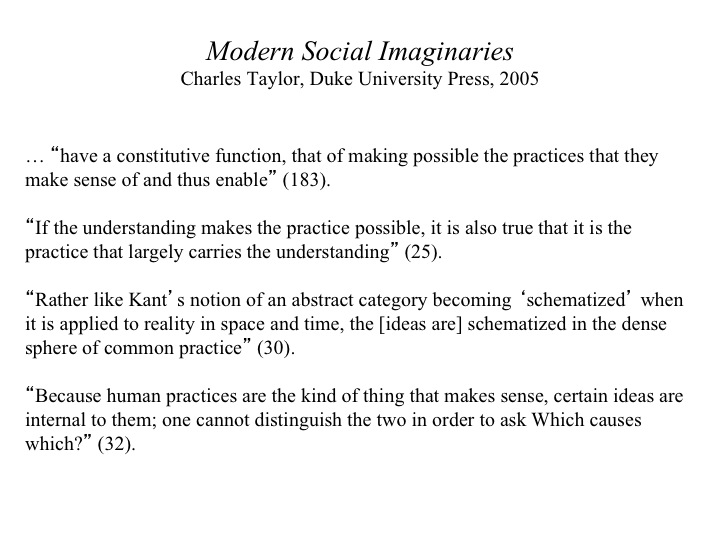

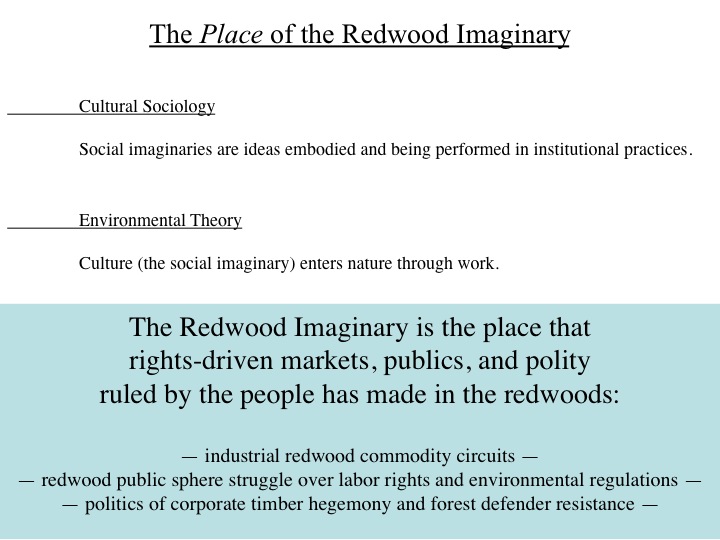

The concept I use and develop in my study to do this work is modern social imaginaries. That is also the title of Charles Taylor’s excellent book on the matter, and of course the concept of social imaginaries is widely used now (how can we forget Benedict Anderson’s Imagined Communities and Cornelius Castoriadis’s The Imaginary Institutions of Society, and so many others, especially Craig Calhoun and Michael Warner?)

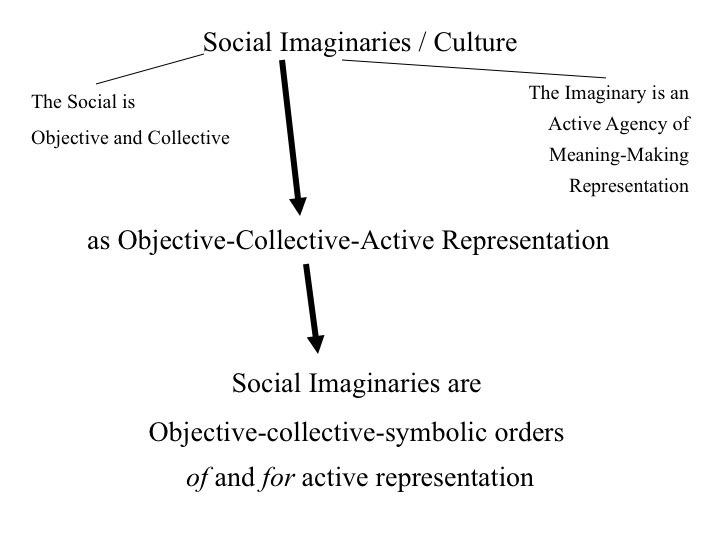

It is a way of talking about culture; it refers to collective self-understandings that are, at the same time, practical, institutional actions, the so-called repertoires common to a social group, the state, nation, or society at issue. They are understandings that are shared and put into action; ideas being performed without necessarily being conscious.

And why not just call them culture? Because the term social imaginary is more useful in the following way: it parses out for us to see the objective and subjective elements that the term culture too often leaves oblique. It refers to values, expectations, norms, beliefs, morals, and ideas of what is good and sacred—but sees these as already embodied and performed in collective, objective institutional practices. Durkheim called them social facts.

The term modern social imaginary moves us beyond the reductionism of either idealism or materialism—that old debate that is starting to sound like a canard; how can we still struggle with that after Bourdieu, Giddens, and Alexander?

Remember Bourdieu’s habitus and field? The dialectic of subjective and objective structures? This term does that same work.

And Gidden’s structuration theory? That’s it!

And remember most importantly of all, the great Marx himself: the great cultural sociologist who said, “Once and idea has been seized by the masses it becomes a material force” —and also, “Man makes history, but not under conditions of his own choosing”.

The term social imaginary carries forward all of this cultural theory.

The social, by definition, is objective and collective, so the term must be read objective and collective imaginary.

But the term imaginary refers to the imagination, which is in every case the active representational, meaning-making activity of a subject. So the term must now be read objective collective active representation.

OK—one final point. In the structuralist movement indebted to the linguistics of Ferdinand de Saussure, the objective collective social order is a symbolic order—an a priori meaning-making system precisely comparable to a language system that subjects put to use, at will.

So now the term is complete: it must be read as follows: Social imaginaries are objective collective symbolic orders of and for active representation.

The social imaginary is thus a usable system of ideal elements already up and running in an institutional structure; a system of meaningful institutions into which people are born and which they therefore tend to embody and naturalize exactly like they do their first language.

This concept applies a linguistic metaphor to all social life, and that is great! Society is a conversation, actually more like an argument.

But my project pushes the idea further and makes the social imaginary into an environmental theory. I create the term redwood (social) imaginary to indicate a local instantiation of the modern social imaginary. It is the modern institutional argument instituted in the redwood ecozone.

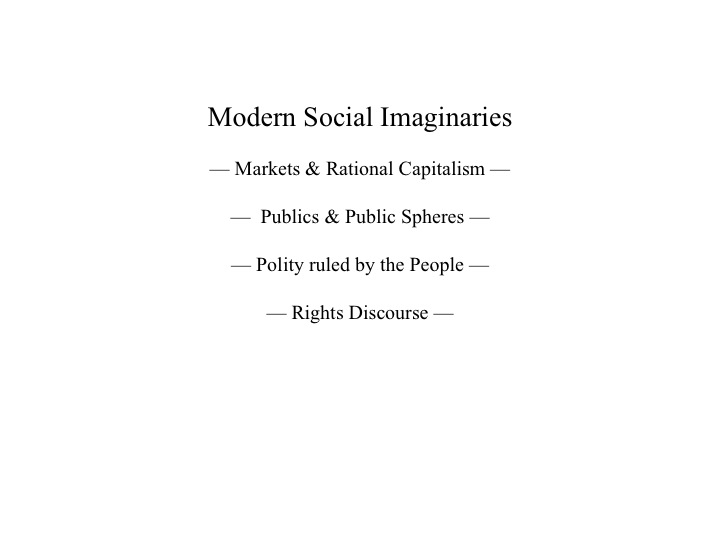

Now we need to define the term modern more precisely. According to Taylor, what is modern about the modern social imaginaries is the rise of markets, public spheres, and polities ruled by the people; these become the dominant institutional domains; and all of this change is driven by a cultural discourse of rights.

These are the dominant institutional tendencies. And what ideas are they performing? At the risk of oversimplification:

First, markets: Capital and wage labor, the two great classes, together in a great and ongoing argument, each presenting an ideology, self-interest versus public interest, liberty as private property right versus liberty as equality guaranteed by the regulated public trust.

Second: publics spheres; free speech exercised in newspapers, telegrams, TV, internet, and mass media, where equality is anchored in openness, representitiveness.

Finally—3rd, Democratic polities; the right rule of law by universal franchise, collective liberty in the form of self-government, collective liberty anchored in the form of collective will embodied in ruling forms of law, governed by the public use of reason.

That is liberalism—liberty and equality in dynamic tension, and so the concept of Modern Social Imaginaries sees modernity as the emergence of liberal hegemony, and history shows its triumph and how it brings on socialization, in the sense of the ever increasing combination of the aggrieved parties in civil society, and also of the rise specifically of socialism, in all of its forms, over and against the expansion of capitalism, the success of which let us not forget goes a long way toward explaining the great fascist backlashes, too, against socialism and communism, don’t forget.

Yes the Nazis moved against the Jews in a total fashion—but the reaction was against the instability of class relations brought on by the rise of capitalism and its unparalleled production not merely of wealth but of misery to go up against it.

The rise of the modern social imaginaries, in their western incarnations as institutional dynamos of markets, publics, and polities ruled by the people, brought economic expansion, yes, but also the crises and the ever more intense waves of expansion and growth as the solution to every successive crisis. It is then its very being globalization! Neo-liberalism! Liberalism for the whole planet!

Remember that these are dominant institutional tendencies only; they are not the only things that are happening. But they are leading the way, and unleashing the most force (history shows that the social has become more marketized, more public, more democratic)(and there is more and more rights talk all the time—there is even a UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights; and there is talk of animal rights and even the rights of nature is are the horizon).

This culture of rights discourse is the founding speech of these dominant institutional tendencies: and in the US, for example, where the Constitution is enumerated in durable text, the engine of rights discourse is particularly powerful. It guarantees perpetual public sphere conflict over property rights and the borders of the market, the border that separates the markets from the public spheres, the private from the public, the political from the economic…. at least to some extent.

My concept of the Redwood Imaginary infuses the concept of modern social imaginaries with environmental theory; we have already named the dominant institutional spheres and the ideas being performed and debated there. Well, according to environmental theory, places are made by imposing ideas on time and space; by schematizing them, you might say, structuring them into the various spheres of practices; or as James O’Connor put it so precisely, “Culture enters nature through labor.”

Markets, driven by ideas of self-interested competition for profits, externalize cost onto labor and environment, entering into them. Market driven alienation and domination produce labor unrest and labor movements; they enter into labor and so into the environment. Then, only expansion of production can defer the ensuing crisis, and more environmental inputs must be consumed to finance the infinite expansion.

According to environmental theory, that is how the first contradiction in capitalism produces the second contradiction: at first, labor unrest and expansion define the dominant contradictory tension; then, following from the continuous growth and expansion the ensuing crisis requires, the 2nd contradiction follows as a matter of course.

In time, they begin to express their historical force and we see the environmental movements emerge.

We have to be brief at this juncture, but: The first contradiction is driven by constant downward pressure on prices, following from the self-interested competition that forces continuous division of labor, increasing scales of production, and the substitution of machinery for labor; wages are driven down as more and more is being produced until crisis strikes at the system from the demand side. This is the so-called realization crisis, and growth (expansion) is always construed by the professional economists as the only way out of the predicament.

But sooner or later accumulating capital strikes at capital from the supply side as well, because the expansion is generating so much external cost that it starts raising the cost of production on capital in general; external costs begin driving up the costs of production in general. There is no cheap old growth in Humboldt county, for example—the deforestation ensuing from the rise of the timber giants and the subsequent revision of the social contract under the compulsion of labor organization, which led to massive increases in production, means that now firms must helicopter the old logs from ever farther up the more and more remote mountainsides.

And logging has ruined the salmon runs; fisheries are collapsing, raising costs in that sector; and now just run with this argument for a second—the atmosphere is heating up, how is that going to raise costs? the oceans are so full of fertilizer from agriculture that in places they sporadically die off, with oxygen depleted dead zones raising the cost of fishing , for example in the Gulf of Mexico and in the South China Sea, where jellyfish swarm by the billions in once rich fishing grounds, decimating other species.

Planetary carrying capacities are being reached all over the place, and people everywhere, under these conditions, are rising up and starting to protect their local remnant ecologies and species and defending their remnant communities of labor, and that is also raising the costs of production.

Under capitalist globalization, understood as the proliferation of rights-driven modern social imaginaries, places all over the world are being made into dangerous places in this way—places whose concrete particular material conditions get structured for the production of resistance. These places become accumulations of grievances—archives of externalized cost and of the terrific struggles that ensue, and which almost always generate violence.

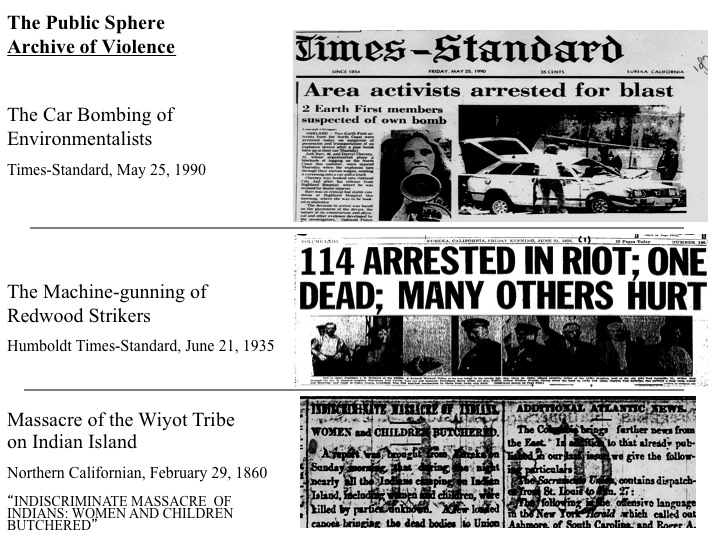

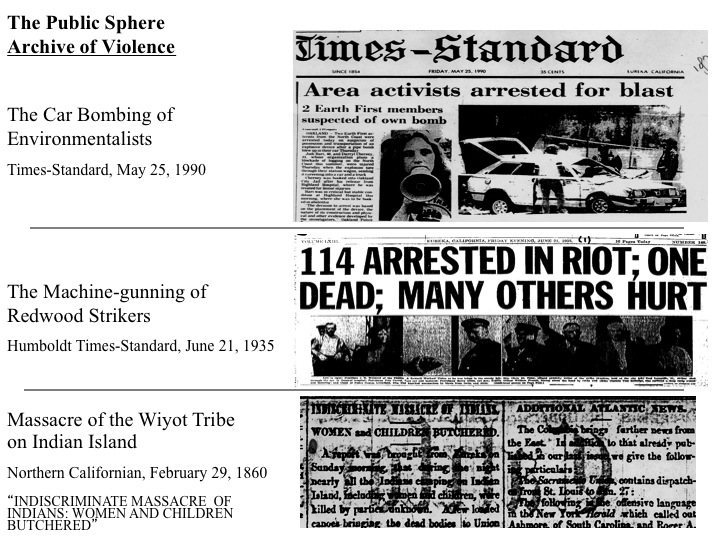

And the violence plays an exceptional role. In the modern social imaginaries, like the redwood imaginary I describe in my book, when unusual violence breaks out, and especially when people are killed, the free speech public spheres and especially mass media seize on the images.

For example, in Humboldt, each of the three epochs of struggle I study in the book produced a signature moment of extra-ordinary violence.

And as an ethnographer of the timber wars, I discovered in countless ways how these events became allegorical of the dominant tendencies and struggles in each epoch—I discovered how the stories are told and retold, and how they accumulate meaning over time, how the texts accumulate, how the tellings and the retellings grow and enter peoples’ lives and identities.

This is how each event entered the public sphere archive of violence and began accumulating and thus increasingly mediating future consciousness, and thus of course future projects and politics.

Today, in Humboldt, you encounter these stories everywhere. For example, talking about the struggle against MAXXAM, conversations almost always lead back to the car bombing; the bombing punctuates the story. When people talk about it, it is like they are always saying, “see, that’s what happens when environmental movements get really radical and then get close to victory by putting peoples’ lives on the line, like in the civil rights movement, that’s when somebody tries to pop them!”

Think of Chico Mendez in the rubber wars; Ken Saro-wiwa in the Nigerian Delta Oil Wars. They almost got Judi Bari. And who will get killed in the Appalachian coal wars? How many others have gone beneath my own radar?

Global ethnographers of dangerous places can tune into the local, place-based modern social imaginary and enter into its archive of colonization, capitalization, and environmental degradation. What they will have there is an encounter with the legacy of rights-driven markets, publics, and polity ruled by the people. And there they can retrieve these images and narratives of extra-ordinary violence and raise them into consciousness and assemble them into dangerous stories about the common conditions and causes of the various peoples’, labor, and environmental movements.

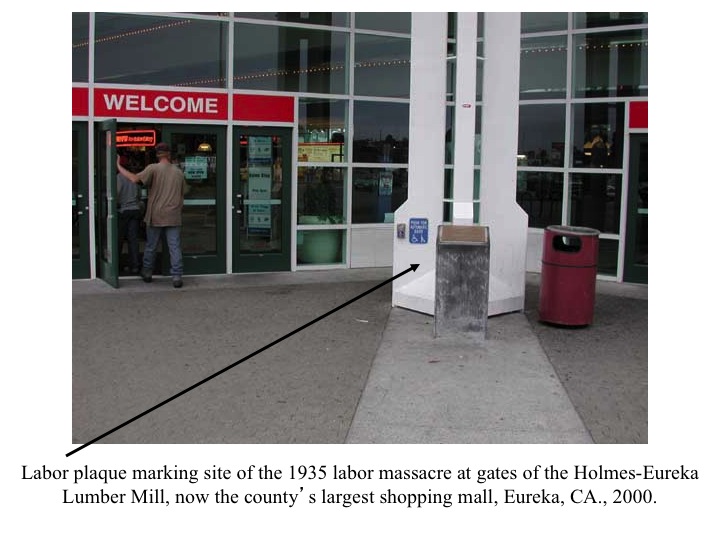

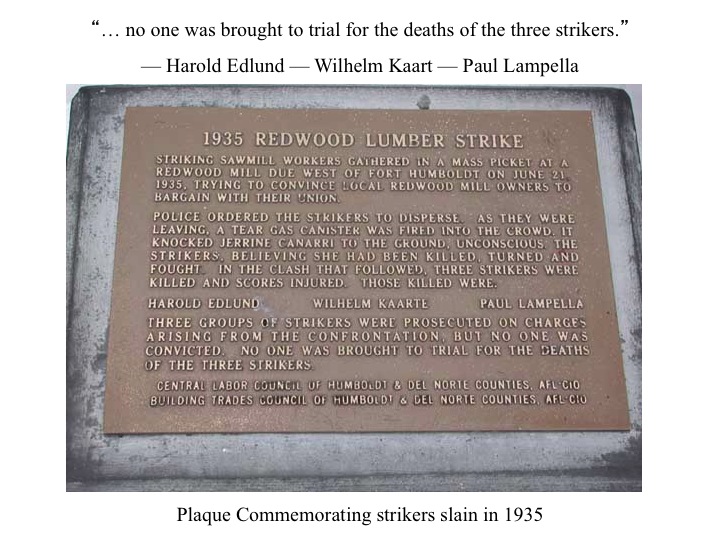

And in Humboldt, there was an archive of labor trouble as well as environmental conflict. There had been very little organized labor resistance to MAXXAM; the unions had been very successfully repressed for 100 years; and conversation about that struggle invariably, almost, similarly lead back to an equally horrific signature moment of violence—it happened during the great lumber strike of 1935, when police backed the capitalists and strikers were machine-gunned. It was an event that the remnants of labor struggle have memorialized and commemorated ever since.

For example here, in this plaque for the slain strikers.

No justice was ever done, that is how the message of the plaque boils down; no one was brought to trial for the massacre. Justice has been promised but not been done.

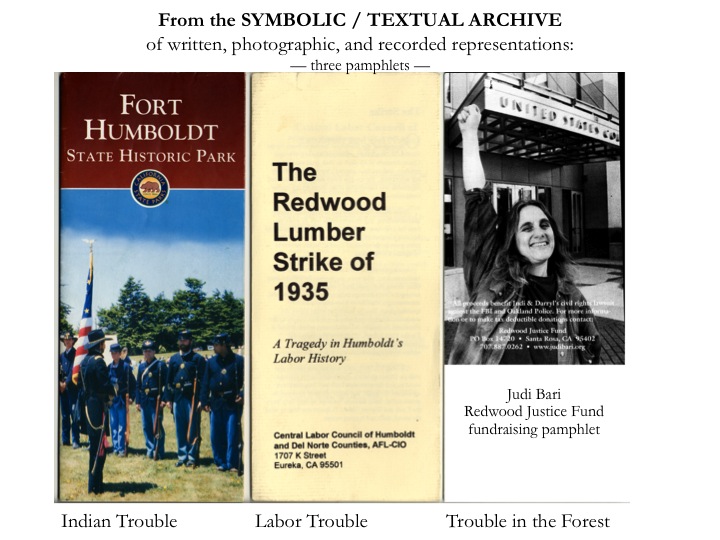

Here, look at the middle pamphlet, “A Tragedy in Labor History”: you see, that is a dangerous story, still today, or at least it is still possibly dangerous to the forces of Big Timber. It exists as a symbolic resource for contemporary consciousness and thus as a tool for political projects and resistance to the ongoing corporate domination of forest practice law.

And what about the land on which all of this history has unfolded?

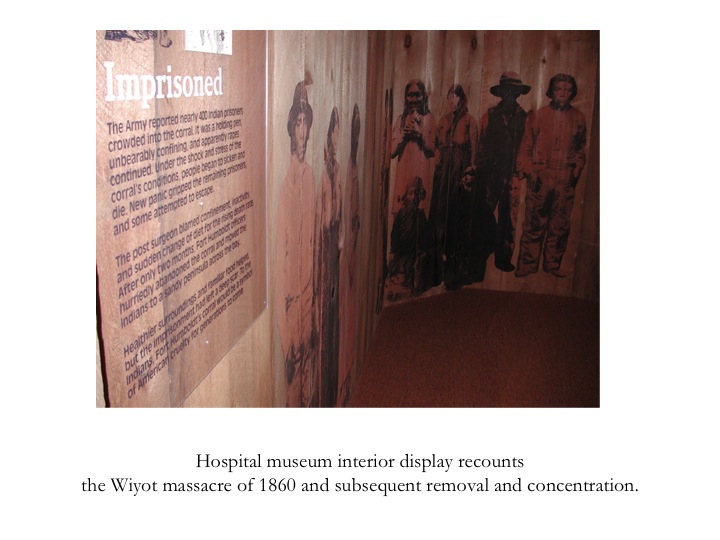

It was Wiyot land—the land that they lost in a story told here, at the old hospital at Fort Humboldt State Park in Eureka. This building has now been converted into a museum documenting the epoch of colnial Indian trouble.

The display inside dramatically retells the dreadful story of that night in 1860 when white men attacked the peaceful tribe at several locations and killed all of the people, mostly women and children, thus completing the reduction of the tribe from about 2000 at first contact in 1850 to about 200 after the massacre. That was a pretty rough ten year period for the Wiyot.

The story of that night now punctuates the story of that epoch; is sums it up and allegorizes it; and it gets repeated over and over, every year, and the descedents of those people use it to articulate their current struggles.

These three signature events become allegorical of their eras; line them up and they map out the stories of primitive accumulation, 1st internal contradictions in capital culture, and then second external contradictions—the environmental contradictions in capital culture.

In my book I have a chapter focused on each event, which I use as windows into each era respectively.

And so, I hope I have shown how global ethnographers of dangerous places can use the concept of modern social imaginaries to tune into the institutional domains of markets, publics and polity and learn to articulate the accumulating grievances of the local archives of colonization by the culture system of capital… Are these other places also accumulating dangerous, violent stories about primitive accumulation, labor struggle, and environmental struggle? Are they really showing the common cause? Are they really growing into potential engines for converging peoples, labor and environmental movements?

I think they are, and global ethnographers need to be trained to see how and to get out there and tell these stories and enter into the movements and help make them real—the future may very well depend on it. I know for certain that Humboldt’s future does.

I wish I had space to explain how all of this is in fact merely preparatory to understanding how the real battle of emergent global civil society is a battle over the mental environment.

These institutions of the Modern Social Imaginary gather together and bind the psychical energies of the masses and channel those energies into the repetition and hence the reproduction of those institutional practices and the ideas they perform: self interest; uber-consumption; unlimited energy use; the overbearing valorization of commercial activity… these are the collective repetition compulsions that prevent thought from escaping and entering into the libratory environmental, labor and peoples politics on which the future depends.