CLIMATE DEADLINE – Paris, December 2015 – with Production and Theory Notes

Climate Deadline – Paris, December 2015

A film by Richard Widick

[IICAT:Edit v5 printed October 5, 2016 revised for new title audio track]

Executive Producers:

Michael K. Dorsey, John Foran, Richard Widick

Director’s Script – CLIMATE DEADLINE – Paris, December 2015 (2nd Draft; 11-7-15)

For Synopsis and Bios, Download the Pollock Theater Program for the October 9, 2015 world premiere

Film Production & Theory Notes

Richard Widick (IICAT:11/10/18)

Climate Deadline. Paris, December 2015. The nations will adopt the next universal climate treaty. That treaty is being created right now. Whose interest will it serve? What can be done?

I’m Dr. Richard Widick, Sociologist, Co-Director of the International Institute of Climate Action & Theory (IICAT.ORG) and Visiting Scholar at the Orfalea Center for Global & International Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and I appreciate your interest in this project.

This work is dedicated to enhancing public participation in the United Nations climate negotiations, at which for the last seven years I have been conducting interdisciplinary participatory observation and ethnographic film research.

The first Conference of the Parties (COP) I attended convened in Durban, South Africa, Dec. 1 -10, 2011.

During two weeks of field research in Durban, I determined to dedicate the next phase of my academic studies to developing a public sociology of the climate talks. At Durban the nations took the decision to start the Paris 2015 work program (then called the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action), and I saw this as the perfect case study in which to exam the panoply of social forces constitutive of emergent global environmental governance.

With my cameras turned on, I returned to COP 18 in Doha, Qatar 2012, COP 19 in Warsaw, Poland 2013, and COP 20 in Lima, Peru 2014—each time again representing the University of California as an official UN Observer Delegate from Civil Society.

Climate Deadline — Paris, December 2015 includes footage from each of these UNFCCC conferences, as well as a number of other events and places that the research took me.

What follows on this page is the near-final fruit of that labor—whereas the final fruit will be a full length documentary film titled Climate Justice that features additional material filmed at the Paris climate conference, November 30 – December 11, 2015, the Marrakech climate conference in November 2016, and the Bonn climate conference in November 2017.

What follows are my notes to the first, urgent release of Climate Deadline (above) on October 9, 2015.

Scrolling down you will find detailed film production, theory, methodology and ethnographic notes intended to enrich the viewer’s experience and understanding of the video documents.

Finally, follow this link to a trailer for the 2019 release of Climate Justice, the movie, which is currently in post-production.

SEGMENT #1 – Opening sound and titles frame the scene:

The opening sound is a sample from five time Grammy Award winning music producer Malik Jusef’s 2014 rendition of Michael Jackson’s “Earthsong.

I met Malik in Lima, where he hosted a release party for the album HOME.

Malik tours with the Hip Hop Caucus, spreading the news and the energy and the music of environmental justice movements across the United States, and we hope to find him again, in Paris, out on the streets pushing back against the old 20th century ways and fossil fuel technologies and promoting 21st century renewable energy technologies.

Throughout the film I strive to use sounds directly recorded or otherwise grounded in the scene of climate business, politics or social movement that is being shown or discussed.

In the current draft of the film I am able to stay true to this only by bending the rule, which the viewer will notice when the tone abruptly shifts from hot background street and radio sounds, protests songs, and driving guitar riffs, to the cool, idiosyncratic and intoxicating ambient music of M. Coleman Horn’s album The Honey Sacrifice.

The sample from “Earth Song” I’m using here perfectly expresses the sentiment of my claim that the global social movement for climate justice has one tool that stands above all others in its symbolic power—something I call The Broken Promise.

The sample opens with the words “The rich and famous. What about sunshine? What about rain? What about all the things that you said we were to gain?”

‘What about all the things that you said?’ — this sentence precisely expresses the formal structure of the demand made by climate social movements.

What about equity, fair shares of the mitigation burden, historical but differentiated responsibilities, climate debt, funding for adaptation, loss and damage, and technology transfer?

What about democratic process, universal representation, and transparency?

These values need reaffirmation in the next universal climate treaty that the Nations are preparing for agreement in Paris.

What about honesty in reviewing the performance of the carbon trading markets we already have—before doubling down with a new treaty that expands what many have already dismissed as a dead end?

Consider that the formal structure of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change is precisely a promise to mobilize and reinforce these values in the service of reducing carbon emissions and mitigating global warming.

To the extent that the UN climate treaty process is captured by fossil fuel interests and comes therefore to represent those narrow sectorial vested interests over and above all other interests, then that promise is broken.

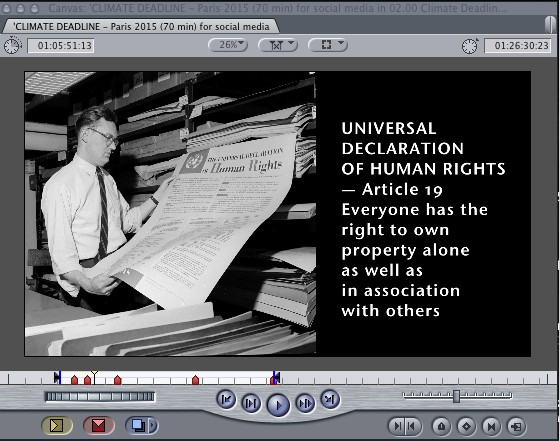

But there is a deeper promise I mean to invoke with this music and this reference—the promise inscribed in the cultural structure of the United Nations itself, which continuously invokes and propounds the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

This is the promise of justice.

And with this promise, the necessary tools for building a future of climate justice are already built directly in to the UN process.

When the movements say, “What about all of the things you say?” — they are invoking this cultural promise.

In the same way, major social movements in the United States have always proceeded by invoking the promise of the US Constitution and Declaration of Independence, which as elements of the founding speech helped call the United States into existence and continues to structure the function of its relatively autonomous economic, public and political spheres of everyday life (practices/culture).

That durable, enumerated, constitutional speech committed the US political body to a perpetual conversation about justice.

On the scene of international climate politics, where climate justice is on demand, this US allegory is informative: in the same way that the founding speech of US nationalism promised that ‘all men (sic) are created equal,’ and so deserve equal standing before the universal law (of natural rights cum human rights) that the state represents through governance, so now does the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights constitute the founding speech of emergent global and environmental governance—in the same way promising the whole package of modern liberal values.

It guarantees those values in practice by granting rights, not merely protecting them but juridically producing them and driving their adoption and propagation to the extent that it legally institutionalizes, for example, property rights-driven economic spheres, free speech rights-driven public spheres, and voting rights-driven political spheres.

With the UN, first, and now the UNFCCC, the Nations put on display and perform a continuous public sphere spectacle of the same modern liberalism.

That is the UN’s promise, its guarantee on the future, and why the UN climate talks must now fulfill that promise by producing a political process and a new universal climate treaty that embodies the values that are inscribed in its constitutional founding speech (UN Charter, Universal Declaration, and UNFCCC Charter, among other documents).

But evidence and experience show that these values are continuously distorted and made to work against the universal interest.

Private interests operate within the laws set up by these institutions to protect their own interests.

And here is the history lesson we need: the UN climate process increasingly relies on and extends the operations and the powers of the very same institutions (the UN, IMF, World Bank, etc.) that programmed the world economic (culture) system for infinite growth via globalization in the first place–growth without environmental responsibility and hence leading to the destruction of the climate system.

These are the same institutions of global economic management that openly argue for globalization based on the corporate free trade agenda.

[For key insights into the relationships between free trade agreements and UN climate policy, especially the new 2015 treaty for Paris COP 21, see Gus Van Harten’s new report]

Defenders of these multilateral institutions tend to argue in classical economic and utilitarian terms that this produces the optimum distribution and hence the best possible measure of economic and social justice.

But the movements point out how deeply the globalization they promote is currently dividing the world into haves and have nots.

The growing, massive inequality they preside over is absolutely mind-boggling.

This is crucial knowledge for the social movements that are trying to get the world back on track for a livable future on an environmentally friendly planet, and it illustrates a problem.

With the deadline of Paris approaching, after which all hopes for a timely, meaningful and adequate collective response to the unfolding climate crisis will start to fade… too many carbon majors and bankers and traders are again doing their best to use the process in the service of their own private interests.

Their efforts are undermining the promise.

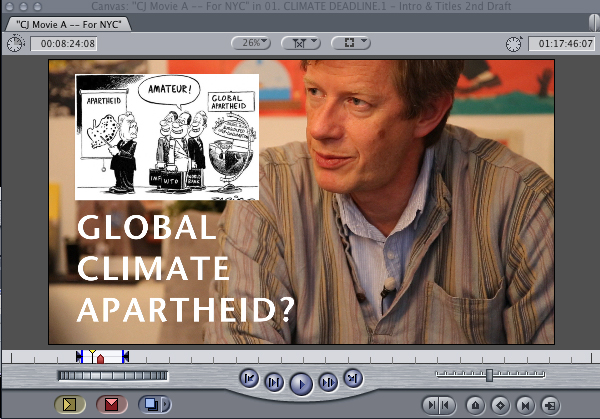

And this raises a question: are we, in and through the UN climate treaty process, laying the foundation for future of climate apartheid—by which I mean inequality in the sphere of climate action? or climate justice—by which I mean fairness in the distribution of climate action burdens and benefits?

With this film, I seek to raise this question to the highest possible urgency.

The full formal title, CLIMATE DEADLINE – Paris, December 2015, is meant to be as simple and descriptive as possible.

NASA Hyperwall image of the sun, recorded by Richard Widick at the US pavilion inside the Warsaw climate talks, November 2013.

By calling the Paris climate conference a Climate Deadline, the title implies that this new treaty will likely be the last best chance to lend the legitimacy of the United Nations—and all of the values that it institutionalizes and broadcasts by way of its founding documents and internal structure—to the struggle for a responsible, global,science-driven and rational collective response to global warming and climate change.

Failure now means decades more of anarchic capital accumulation at the expense of the atmosphere, the oceans, the forests and the species—and especially the least well off human beings already living on the margins of the fossil fuel-driven globalizing world economic (culture) system.

In the opening series of interview vignettes, this urgency is captured in the poignant remarks of four scholar activists I met and filmed in the course of this study.

Dr. Michael K. Dorsey of the Joint Center for Political & Economic Study, Washington DC, and a Director at the Sierra Club:

“The true story of 21st century climate policy,” according to Dr. Michael K. Dorsey, “is the story of corrupt corporations—recidivistic corporate criminals shaping the policy.”

This is readily apparent in the case of domestic US policy and participation in the UN climate talks, a scene on which the corporations continue to mobilize fantastic sums of money at every scale to protect their interests, as they have done since they helped successfully prevent US ratification of the 1977 Kyoto Protocol, and which they continue in their constant Congressional lobbying efforts pushing back against the President Barack Obama’s more progressive policy initiative, for example his new power plant regulations.

According to Dorsey, we cannot understand the struggle over the next universal climate treaty—its weak ambition (2 degrees maximum average warming target, versus the African nations’ demand for a target of 1.5 degrees); its lack of enforcement mechanisms; its reliance on failed carbon trading schemes, etc.—without speaking the truth about the actions and records of these corporations, among whom he includes both private and state run entities (especially the so-called carbon majors; the report; press release; methods and results report).

The ways in which fossil fuel companies shape the policy is well documents: see especially the Union of Concerned Scientists ‘ July 2015 report The Climate Deception Dossiers; read their page releasing the report and Andrew Revkin’s report in the NY Times;

Camila Moreno of Grupo Carta de Belem, Brazil:

“It’s a problem we are seeing everywhere,” Camila Moreno told at COP 20 in Lima, “which we call it, we name it climate structural adjustment. Legal frameworks like the mining code, the forest code, new legislation for example on the sense of regulating environmental services so-called are being created everywhere. In Latin America this process has been overwhelming over the last four to five years. Every country has had their legislation changed, and people were believing that this was for climate protection, when actually it was for the creation of new property rights over a new class of assets, over ‘intangibles.’”

I met and interviewed Camila Moreno for the first time on Saturday, December 12, 2014 outside the main plenary hall at the Lima climate talks.

As she explained how states and economies are changing their laws and practices to further monetize ecosystem services, making them tradable in ways that can be used to shape outcomes (incentivize mitigation, adaptation, and investment in renewables, etc.), and naming theses changes climate structural adjustment, I realized she was giving a well developed theoretical primer on something I was just beginning to conceive for myself.

One of my central theses in this film and my essay Climate of Empire concerns the transformation of UN climate policy along lines comparable to that of UN economic policy between the 1970s and 1990s.

In that earlier period, UN-led institutions of global financial management sought to aid developing countries develop more rapidly, and rationally, by supplying, among other things, loans.

When countries ran into trouble paying, they would often be forced to refinance under conditions of neoliberal “structural adjustment programs” (SAPs) designed by the IMF and World Bank to liberalize their economies.

Simply put, if the debtor nations wanted their loans extended, or additional loans under favorable terms, they had to give something back.

The international financial institutions demanded reforms that today we would call ‘austerity measures,’ for example reduced pubic investment in social welfare, healthcare, infrastructure, public education, etc., as well as privatization of state assets in sales open to foreign entities.

The sad result was debt-imposed shopping sprees among the debtor nations by massive corporations backed by rich northern governments.

Read about this in the superb essay “Planet of Slums” by Mike Davis (Verso, 2006), especially SAP references on pps. 15, 62-3, 84, 125, 148, 152-162, 163, 174, 177, 180, and the case of Congo 192-3.

The coming Paris climate treaty has been hailed by centrist thinkers for its novel, hybrid ‘bottom-up’ (pledge and review) and ‘top down’ (science-driven collective emissions targets) — but how much of the Nations’ voluntary (bottom-up) pledges will be geared for using market mechanisms reliant on these legislative climate structural adjustments? will the projects that produce mitigation and thus earn tradable carbon credits start out as ‘voluntary’ but then, when the targets are not met, transformed into carbon credit obligations that can be made conditional structural adjustments in the same way that IMF and WB loans were in the economic SAPs previously “offered” to the debtor, un- and still-developing Nations?

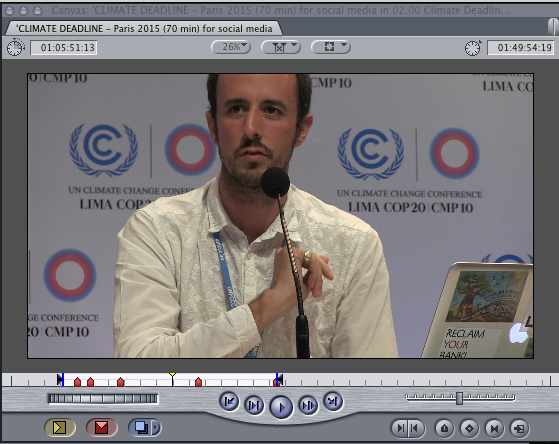

> Climate Structural Adjustment, speculation with notes to follow… Cite my remarks at 2014 UN Press Conference at Lima, COP 20.

Patrick Bond, Center for Civil Society, KwaZulu Natal University, Durban, South Africa:

According to Patrick Bond of the Center for Civil Society, whom I interviewed at COP 19 in Warsaw 2013, “South Africa had racial apartheid, where the key division was the race line. It shifted. We’re now in what I would call South African class apartheid. The key division is how much money you have, and if you are in a circuit where your money and your race gives you the kind of access and the networks to live a good life while more people are suffering in socio-economic terms. And in the future, climate apartheid will certainly work along race and class gender lines in very important ways.”

Mithika Mwenda, Executive Director of the PanAfrican Climate Justice Alliance:

“We look this as a struggle,” said Mithika Mwenda when I interviewed him in Oakland, California during his US tour with the Pan African Climate Justice Alliance in early 2014. “And what the difference between this and the anti-apartheid, anti-slavery, and anti-colonial movements was that this is bigger than that. We are fighting a bigger force.”

Richard Widick, Sociologist, Orfalea Center for Global & International Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara—presently researching, writing, directing, shooting and editing this film:

As you know by now, my name is Richard Widick.

I am a Sociologist at the Orfalea Center for Global & International Studies, the narrator of this film, and author of Trouble in the Forest: California’s Redwood Timber Wars.

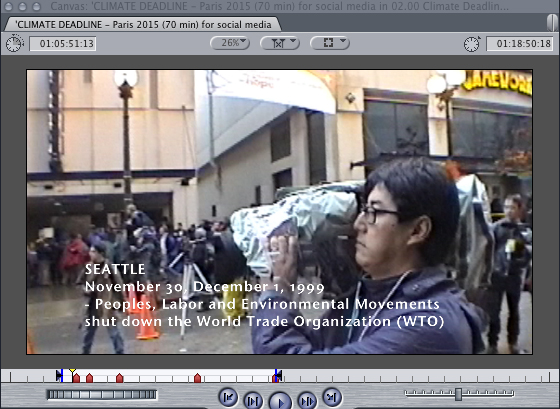

As a graduate student in Sociology at the University of California, Santa Barbara, in September of 1999 I set out to do field research for my dissertation on the struggle to save California’s last remaining north coast old growth redwoods.

When I arrived in Humboldt County, on the north coast of California, intending to get involved in the struggle, the first thing I discovered was that most people in the ancient redwood forest defense movement were preparing to head up the west coast to Seattle and protest what became the World Trade Organization’s infamous ministerial conference.

As a conflict seeking, participatoiry ethnographer, I got right on board.

First I attended nonviolence training with redwood forest defenders and United Steel Workers, who were at that time building the Alliance for Sustainable Jobs and the Environment.

The idea was the same everywhere—indigenous and poor peoples’, labor, and environmental movements in alliance against the World Trade Organization’s free trade policies, which people understood clearly privileges the corporations and promotes their concentration of private wealth, while undermining the global labor and environmental commons.

“Fair trade, not free trade,” one of the slogans widely heard in Seattle, nicely encapsulates the sentiments of collective resistance that made the event into a truly world historical rupture of the status quo.

So I went to Seattle with my cameras and my notebooks, and my training in theories of culture and social movements, intending to bear witness and enter the fray.

It was the first time I had turned on my video camera for sociological field work.

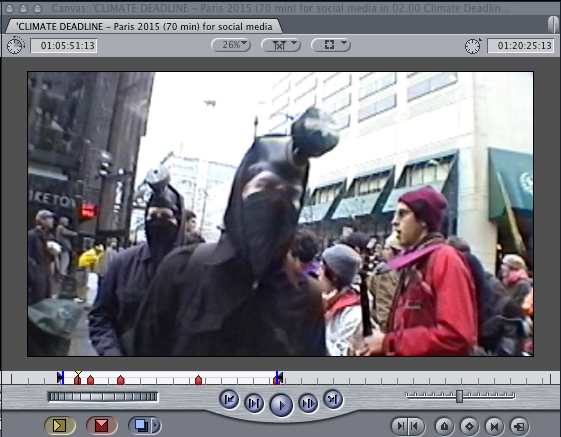

I spent four days on the street, ultimately shooting more than 20 hours of video on what was at that time a state-of-the-art Sony Hi8 Handycam (maximum resolution 640 x 480 pixels).

Over the following two years living and doing ethnographic fieldwork in Humboldt, I became increasingly fascinated with these images.

Every time a new dimension of my analysis opened up, I could find references to it in this archive of footage.

This remains true to this day, as now I anchor this film in a history lesson narrated against the backdrop of this incredible street protest.

In the background, Bonnie Raitt is singing “War on the Workers,” which sound I recorded on my handheld Panasonic DAT recorder while participating in and documenting one of the street marches in Seattle.

I use that song, and the street noises she was forced to be singing over, along with at least ten additional sound tracks.

One of my favorite images from this scene shows members of the Black Block, anarchists wearing gas masks and making trouble for business owners and police alike, cutting through a group of youthful environmentalists marching as they sing the Wobbly labor hymn “Dump the Bosses of Your Back.”

Dump the Bosses Off Your Back

by John Brill (1916), from the IWW Little Red Song Book

Are you poor, forlorn and hungry?

Are there lots of things you lack?

Is your life made up of misery?

Then dump the bosses off your back.

Are your clothes all patched and tattered?

Are you living in a shack ?

Would you have your troubles scattered?

Then dump the bosses off your back.Are you almost split asunder?

Loaded like a long-eared jack?

Boob – why don’t you buck like thunder,

And dump the bosses off your back?

All the agonies you suffer

You can end with one good whack;

Stiffen up, you orn’ry duffer

And dump the bosses off your back.

As the Anarchists cut across the line, the song is sung by young environmentalists, not union men and women, capturing precisely the essence of all three of the constituencies that made Seattle 1999 into a world historic rupture of the status quo: the convergence of peoples (in this case disaffected urban youth), labor (the song), and environmental movements (the singing environmentalists).

Since that time I have used this phrase — “converging peoples, labor, and environmental movements” — to describe what the big UN economic and climate conferences are doing to and for the anti-globalization, social justice, and now climate justice social movements: namely, is calls them out, into action, into the public sphere, where they come together, meet each other and grow.

Grabbing the media spotlight, they grow into global spectacles of emergent collective subjects–social forces, in other words, acting and shaping at least in some small way the also emergent institutional apparatuses of permanent global economic (IMF, WB, WTO) and environmental (UNFCCC, UNEP, etc) governance.

Further notes on Segment # 1 to follow …

SEGMENT # 2 – The Present Historical Moment of the Global Climate Politics

Theoretical Voice Over script to follow …

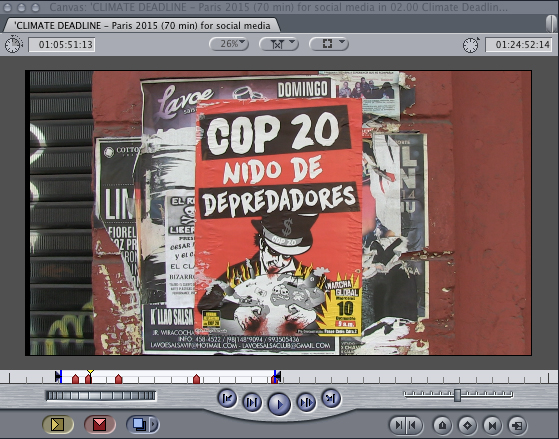

“Nest of Predators” notes to follow … See Oxfam — Working for the Few – Political Capture and Economic Inequality — 2014 citing the most incredible statistic: today, 85 individuals own as much social wealth as does the bottom one half of the world’s population.

Social production of wealth and misery… in equal measure?

Global stratification notes to follow …

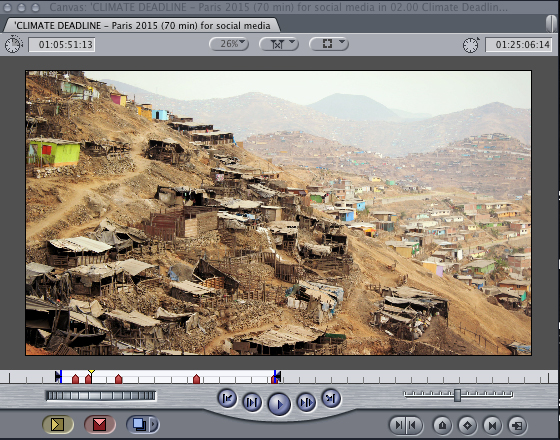

The SETTING: Lima, Peru, December 2014

10 Million people breathing Latin America’s worst air. 3 million people living in the worst of slums, a city alive with concentrated wealth and brutal poverty, torn by contradictions, driven by violence and beauty.

A perfect setting in which to investigate the philosophy of climate justice.

Lima notes to follow. See Mike Davis, Planet of Slums (Verso, 2006).

The UN Charter

UN Charter notes to follow …

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights …

Human Rights notes to follow … See my essay “Invitation to Paris“for extended discussion of how written constitutions and charters function as founding speech to juridically organize rights-driven, relatively autonomous spheres of economic, public, and political practice within the broader playing field of what might plainly be called everyday life in the modern world.

QUOTE: “The victors of WWII set the stage for their own post-war domination of global politics, markets, and even public sphere participation in both national and international affairs when they expressed their triumph juridically in the legal constitution of the United Nations.

I will argue in what follows that their principal creation—the UN as a rights-driven set of juridical institutions, with a constitution/charter in the liberal democratic republican form—can be and should best be understood in its symbolic function as a broadcast or messaging machine for inviting the world to join the struggle in favor of liberal democratic system. It is a public drama of the Enlightenment liberal ideal.

That is the philosophical key we need—we need to see the whole UN process as what Jacques Derrida called a philosopheme.

Please allow me to quote Jacques Derrida at length from The Right to Philosophy (Stanford University Press 2002:3-4):

“These [UN] institutions are already philosophemes, as is the idea of international law or rights that they attempt to put into operation. They are philosophical acts and archives, philosophical productions and products, not only because the concepts which legitimate them have an assignable philosophical history and therefore a philosophical history which is inscribed in UNESCO’s charter or constitution but also, by the same token and for that very reason, because such institutions imply sharing a culture and a philosophical language. And from that moment on, they are committed to make possible the access to this language and culture, first and foremost by means of education. All the States that adhere to the charters of these international institutions commit themselves, in principle and philosophically, to recognize and put into operation in an effective way something like philosophy and a certain philosophy of rights and law, the rights of man, universal history, etc. The signature of these charters is a philosophical act which makes a commitment to philosophy in a philosophical way. From that moment on, whether they say so or not, know it or not, or conduct themselves consequently or not, these States and these peoples contract a philosophical commitment by dint of joining these charters or participating in these institutions. Therefore, these States contract at the very least a commitment to provide the philosophical culture or education that is required for understanding and putting into operation these commitments made to the international institutions, which are, I repeat, philosophical in essence.”

So the UN itself, and by extension its subsidiary UNFCCC, are philosophemes—and what is the culture that they share?

What is the philosophical language or content that legitimates them and makes them what they are?

The culture of natural rights cum human rights, among which one in particular deserves attention for the powerful social forces/subjects it calls into being and drives unto the ends of the earth:

Private Property, set up institutionally and guaranteed juridically by modern nation states is taken up and rearticulated, redeployed, on the global scale in Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Juridically institutionalized private property rights-driven economic development notes to follow … see my Trouble in the Forest, pps. 8, 9, 10-13, 25-29, 33, 55, 65, 71, 74, 76, 78-79, 126, 140, 142, 229, 231, 235, 244, 265, 268, 280, 290-298, 309n41.

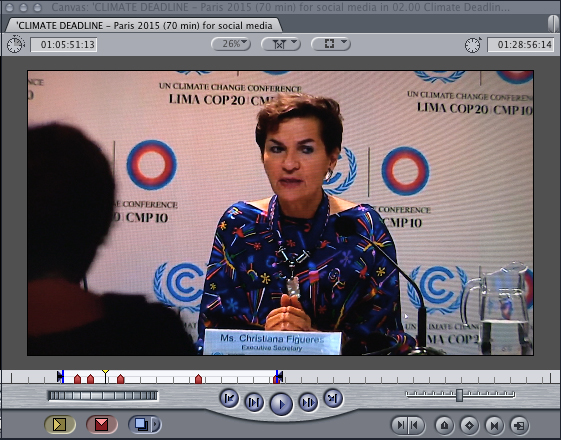

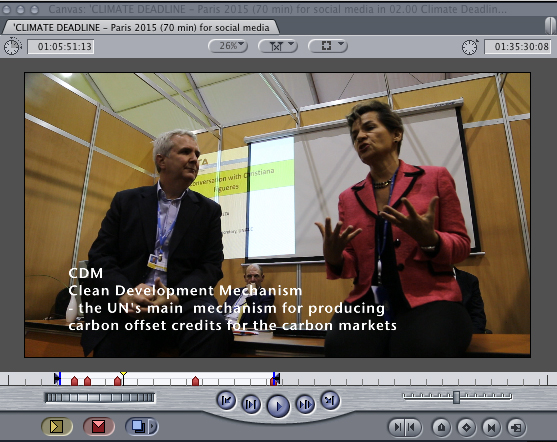

Christiana Figueres, Executive Secretary, United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and very widely-respected expert on the climate politics and processes of the annual Conferences of the Parties (COPs), here describing the negotiating work being done in Lima at her opening press conference, COP 20, Lima Peru, December 1, 2015.

Figueres notes to follow …

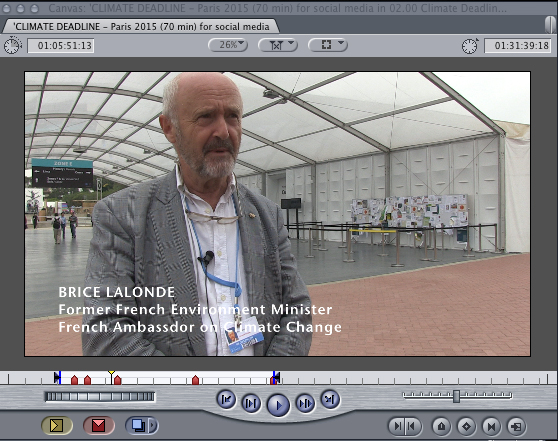

Brice Lalonde …

Lalonde notes to follow…

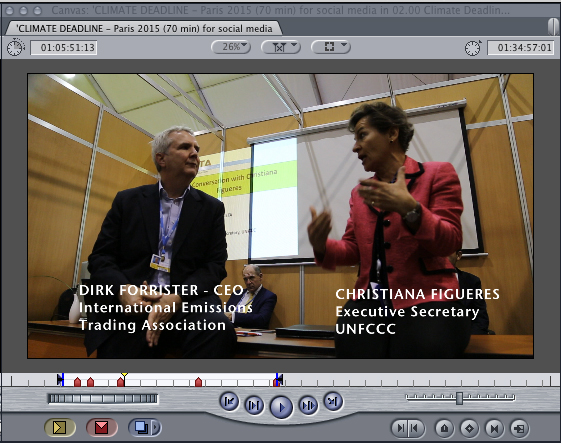

Dirk Forrister, CEO of the International Emissions Trading Association (IETA) together with UNFCCC Executive Secretary Christiana Figueres at the IETA pavilion inside the Lima climate talks…

Forrister, Figueres and the IETA notes to follow …

Michael K. Dorsey explaining that markets fail to distribute public goods in an equitable fashion …

Market notes to follow … See Dorsey’s essay “Fear and Loathing of Carbon Markets” (IICAT 2014).

Pascoe Sabido of Corporate Europe Observatory, who appears briefly this opening montage, is great source for information and analysis on this difficult subject. See for example the 2014 CEO Report Corporate Conquistadors.

Key sources: CEO’s report Corporate Conquistadors.

Camila Moreno, explaining the rise of new hegemonic powers that reaffirm and reboot old colonial dynamics….

BRICs notes to follow …

Forrister and Figueres on the UNFCCC’s Clean Development Mechanism …

CDM notes to follow …

Dirk Forissiter on the nirvana state for business, full marketization …

Carbon trading notes to follow …

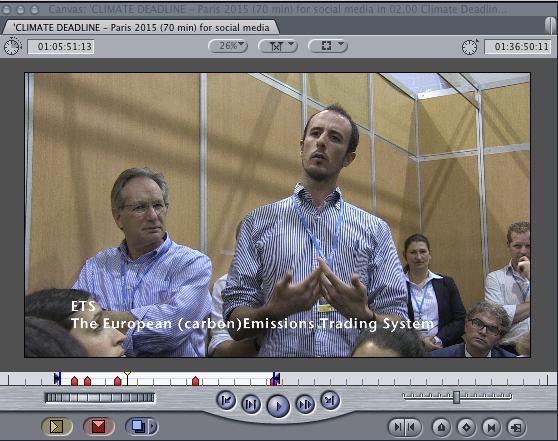

Pascoe Sabido at UN PC explaining the failure of European carbon markets…

Notes evaluating the performance of existing carbon markets to follow …

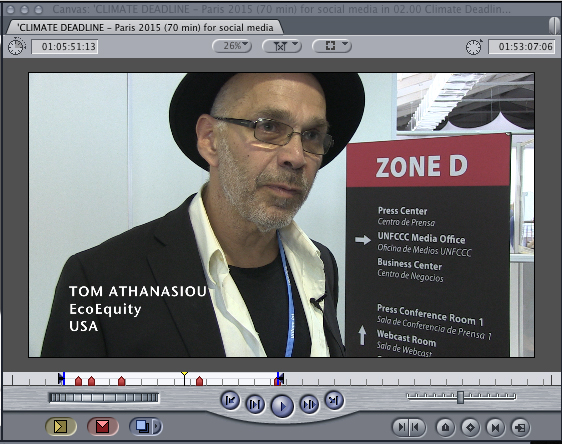

Tom Athanasiou of EcoEquity and Climate Action Network explaining the role of equity in the new treaty ..,

Equity notes to follow …

Godwin Ojo, Friends of the Earth International, Nigeria on the case of Ogoniland …

See also Godwin’s RadioMondial interview of July 8, 2015: the terrible story of Shell Oil in Nigeria.

Ogoniland notes to follow … see my Trouble in the Forest pps. 1-25, The Introduction, Sections Property and Place (10-13) and Landscape and History (20-25).

If, as James O’Connor writes with terrible concision, “Culture enters nature through labor,” what does the social and ecological landscape of Ogoniland say about the colonizing culture of fossil fuel-driven private property right-driven markets in the 21st century?

Climate action peoples march, street scene, Lima, COP 20 2014 ….

Climate march in Lima notes to follow ….

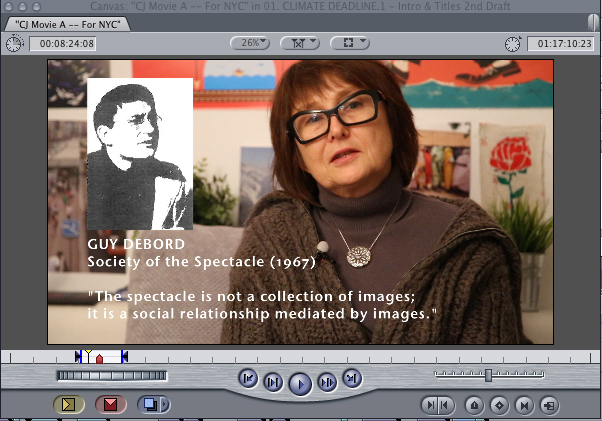

Ewa Charkiewics, Feminist ThinkTank, Warsaw, Poland … See especially her remarks on the “spectacular dimensions of the climate talks.”

Throughout these film production and theory notes you will find that I constantly return to this concept of the Spectacle.

On my IICAT Research Archive MAIN PAGE, dedicated to my manuscript Climate of Empire, I introduce the concept as follows:

UN CLIMATE NEGOTIATIONS AS GLOBAL SPECTACLE

Reading my working papers (see my research archive), you will find that my principal efforts thus far are focused on the UNFCCC and its annual Conference of Parties—a ritual gathering that I see as crucial because it functions to convoke the corporations, the movements and the nation states in a planetary Spectacle of conflict that dramatizes the basic social and ecological contradictions built in to the globalizing world economic (culture) system.

The spectacle of big UN international climate conferences thus serves the pedagogical function of educating us, the public and everyone involved, in the complexities of carbon-industrial modernity and its accumulating effects on the Earth’s basic life support systems—its air, water, forest, and ocean systems and its diverse multitude of living organisms.

The spectacular conferences, serving as meeting grounds for converging peoples, labor and environmental movements, serve as arenas for these movements to educate themselves about each other, to identify their concerns, and so to focus their combined attentions.

In this way, the yearly drama of UN Climate COPs become more than just the target of global civil society—they grow increasingly constitutive of that global civil society.

They are engines of global civic engagement, and their relevance must be appraised as such and not merely on the grounds of their own internal progress towards their own internal objectives.

The more I watch the world’s economic, civil society and state actors grappling over climate governance under the auspices of the United Nations climate negotiations, the more I believe that our collective future hangs in the balance of this model cosmopolitan experiment in international cooperation.

Here’s the point: The Spectacle is a name for the social relationship that is Globalization itself—the expanding carbon-fueled world economic (culture) system.

But, to be sure, as Guy Debord wrote in his 1967 film The Society of the Spectacle, “The spectacle is not a collection of images: it is a social relationship mediated by images.”

It is the relationship of capital to labor — mediated by images.

Seen through this theoretical lens, the Spectacle of the UN climate talks appears as a paragon of (economic) development politics.

They are a premiere embodiment of the two great contradictions confronting the infinite expansion of the world economic (culture) system: the first, internal contradiction is that of labor; the second, external contradiction is that of environment. Read more on the first and second contradictions >>>

Climate of Empire (the book) and Climate Deadline (the film) both begin by studying the Spectacle of the UN climate talks as an expression of these contradictions; they are the empirical data out of which the speculative theory it built.

Rachel Kyte for the World Bank at the mic, while Camila Moreno quotes her from Lima COP 20, “This is about reengineering the world economy” and “commodification of the air, water, forests, and most of all carbon.”

World Bank role in the climate talks, notes to follow …

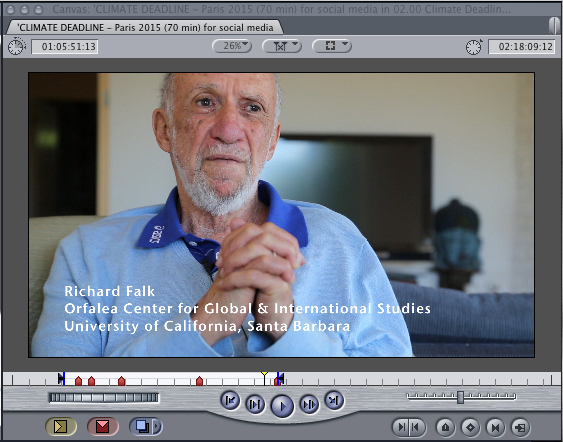

Richard Falk on the necessity to radically challenge neoliberalism in the emergent world order represented by the UNFCCC climate process ….

Mithika Mwenda on the coming hurricanes of people power …

Call to climate action at Paris COP 21, December 2015, notes to follow …

:ADDITIONAL BACKGROUND, before October 2015:

The nations will adopt the next Universal Climate Treaty at the UNFCCC COP 21 in Paris, November 30 — December 11, 2015

That treaty is being crafted right now, and should be ready for preliminary debate at the final Bonn Climate Conference before Paris will be October 19 – 23, 2015. Follow it at IISD.

WATCH UNFCCC Secretary Christiana Figueres explain “The Road to Paris” at the Australian National University, Canberra, 0n May 7, 2015—a public lecture that she begins by saying “I will now explain why in fact things are going so well.”

The current Negotiating Text of the treaty is still dated February 25, 2015, but as Bloomberg reports on July 24, the Co-Chairs of the ADP edited down that 88 page so-called Geneva Negotiating Text (GNT) of February 25th, 2015 to 19 pages — read this 19 page Skeletal Paris Agreement and the Draft Decision in the July 24, 2014 Scenario Note on the 10th Part of the 2nd Session of the ADP, which was prepared by the Co-Chairs the next Bonn climate talks August 31 – September 4, 2015.

[see also the June 11, 2015 “Streamlined and Consolidated Text” from Bonn]

The draft prior to the February 25 GNT, published on February 12, 2015.

The first draft appeared as an Annex in The Lima Call for Climate Action, the outcome document from the COP 20 in Lima, December 13, 2014, under the official title Decision -/CP.20 The Lima Call to Climate Action.

See the archive of Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) that have been submitted.

Read the European Union’s INDC .

Read the US – China Bilateral Agreement (announced before COP 20 in Lima, 2014).

See also the European Union’s 2030 Framework.

The International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) is reporting on the Bonn Climate Conferences up through Paris COP 21, December 2015.

Follow it all on the IISD Climate Change Policy and Practice feed.

FOLLOW Richard Widick’s DETAILED NOTES on the production of the new treaty.