Invitation to Paris: Answering the Call of the Law of the Nations to Participate in Emergent Global Climate Governance

— working paper —

Richard Widick, PhD

Director, International Institute of Climate Action & Theory

Visiting Scholar, Orfalea Center for Global & International Studies

University of California, Santa Barbara

richard.widick@orfaleacenter.ucsb.edu

An early version of this paper was first presented at the Orfalea Center for Global and International Studies on May 19, 2011 under the title “Invitation to Durban: Ethnography and the Politics of Climate Activism at COP17,”

Revision, August 10, 2022

— INVITATION TO PARIS —

On Answering the Call of the Law of the Nations to Participate in Emergent Global Climate Governance

Climate Deadline, Paris, December 2015 — the nations were called upon to adopt the first truly universal climate treaty at the upcoming Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC COP 21, convened in Paris, November 30 – December 11, 2015)

They did adopt it.

And you were invited to attend… but it was not an invitation in the common or casual sense of that word.

Instead, the invitation I’m referring to came inscribed in the cultural form of the structure, if you will, of the entire system of international climate negotiations.

I claim that we stand in relation to the UNFCCC process as we do before any and all cultural systems—and that we should treat it as such—as a cultural system that confronts us precisely like a language (that is the model we should apply to everything, as cultural sociologists, following Saussure).

Here is how it works: What do you do with any language? You use it. You use it to make meaning. But to do so you have to follow its rules. That is the force that it exerts on you. That is what it expects and demands of you. It does not tell you to say this or that. It does not control your speech. Rather, it establishes the fact that to say anything at all, if you want what you say to have meaning within the linguistic community established by that language system, you have to use the words that it supplies and that it recognizes and the grammar that it provides and enforces.

Here is something that is true about every language (and thus true about the system of international climate negotiations): as they pertain to any concrete specific individual in any specific time or place, they are always experienced as already up and running. We are thrown into them and encounter them as objective meaning-making systems that are already up and running and exercising objective forces over us, addressing us, and expecting us to respond, properly and in kind.

In cultural sociology, we talk this way about being born, or thrown, into a particular cultural form of family institution; about being born into hospitals and the whole cultural system of the medical establishment; about being thrown or sent as children into the school system; about being subjected as children to various religious systems; about being required to work in the economic system; the market system; the labor system; and in general about how all of these cultural systems are always already nested within this or that national cultural system, which itself has this or that Constitutional package of basic institutional rules. Can you hear the echoes of Foucault’s carceral archipelago here? (see the last chapter of Birth of the Prison in this regard).

But also think of Roger Friedland’s excellent point about how modern people tend to experience freedom as movement between the various institutional fields of power.

At any rate—now it turns out that the world is heating up, and we are all waking up to that fact and discovering that we have been born or thrown into a world in which a global system of governing institutions is already up and running an international system of climate negotiations—do not forget that COP 21, at which the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change was adopted, came at the 23rd anniversary of the 1992 Rio Conference on Environment and Development, at which the nations adopted the Rio Convention establishing the UNFCCC. So this is nothing new—but now many people are just waking up to this fact and just now beginning to realize the seriousness of the whole thing… three decades after the fact!

And the UNFCC as a cultural system is still addressing them, addressing us, with the force of an invitation. It is still expecting us all to respond.

Now—the force and character of any invitation is inscribed in the customs or laws that govern both its potential usages and the accumulated archive of their past usages; together these function like a grammar and a lexicon. Thus, for example, one could wage a human rights campaign in the US today, let us say for the right not to be tortured or held indefinitely without trial—and to do so you would have to make a claim on a certain right: “I am a citizen,” you will say, “with a right to my body and my health and to a fair trial!’ But, what would be and what could be your meaning here? This perspective in cultural sociology makes us ask “Meaning for whom?”

You know what you meant—but meaning is made not just at the point of speech (production), but also by the conditions under which that speech then goes into circulation (exchange), and by whom receives it and responds (consumption and [re]production]). Once uttered, it turns out, your meaning is not your own but rather takes on a life of its own.

And so the accumulated archive of previous usages bears down on us. The archive of human rights campaigns in the US, for example; the Anti-Slavery Movement; the Civil Rights Movement; the American Indian Movement; the Labor Movement; the women’s movements—all of the these movements and more together have built up a massive public archive of accumulated rights claims, the meanings of which are part of an objective cultural system that you can and in fact must use to make your new claims meaningful, just as the people who respond to you will use it to interpret your speech and respond anew.

As ethnographers, we can apply this cultural-theoretical perspective to the UN in general, and to the UN climate negotiations in particular. The theory is a method to record and interpret the negotiations and comprehend the politics of the climate activists, who on one side are responding to its invitation intent on protecting the global commons and defending the ability of local communities of labor to muster normative interventions in the governance structures that determine so much of their daily lives, as well as the politics of neoliberal globalizers, who on the other side are responding to the same invitation intent on intensifying market rule and eliminating obstacles to the pure market logic of privatization, accumulation and concentration of all values (Ciplet and Roberts 2017, esp p. 149).

In order to formulate our questions and start gathering our data, we need to get oriented.

Consider the fact that the UNFCCC, under UN auspices, is an experiment in global self-governance, created after WWII by the victors, which were united to some extent in victory, by the way—but not totally united ideologically. Recall that Russia and China were included from the start (essentially the UN represents the alliance of socialist, democratic and nominally ‘communist’ nations over and against fascism).

What was it created for? To oversimplify, it was intended to prevent WW III, largely by managing and regulating economic relationships, which had become encumbered by multiple national tariff regimes, for example, that exacerbated the struggle for resource extraction in the various colonies of the various powers, and everywhere else for that matter—whatever and wherever had not yet been internalized within the expanding world economic (culture) system (of globalization). But not by founding a communist order. Not by creating an new axis of socialism. US and allied powers rather modeled the new system on the science of liberal democratic republican institutions of self-government through consent, and they seated it in New York City. The UN’s idea of itself has always been as a bastion of the free world, the open society, even if that idea was contradicted from the start by inclusion of nation-states that did not at that time and have not since measured up to that idea.

That idea functions in reality as a regulative ideal (in the Kantian sense)—no societies have fully achieved the promises inscribed in the UN charter and its Universal Declaration of the Human Rights, but the ideas and promises expressed therein, functioning as a regulatory ideal, guide the effort to assemble the systematic unity toward which society is led by the public use of reason for rational polity. And let us set aside for the moment what could be said about the relation of that ideal to US activities in Korea; Vietnam; Laos; Cambodia; Iran (in the 1950s); Iraq (in the 1960s); Cuba; Chile; Nicaragua; Guatemala; El Salvador; Costa Rica; Grenada; Iraq again in the 1990s and continuously through the decade of sanctions to the second invasion in 2003, and the ongoing war up through the present, Afghanistan…. Etc. Etc. Etc.

Here is my point: The UN was modeled after, dominated by, and meant to shore up the social-democratic-capitalist forces over and against the anti-democratic capitalist fascist tyrannies.

The victors of WWII set the stage for their own post-war domination of global politics, markets, and even public sphere participation in both national and international affairs when they expressed their triumph juridically in the legal constitution of the United Nations.

I will argue in what follows that their principal creation—the UN as a rights-driven set of juridical institutions, with a constitution/charter in the liberal democratic republican form—can best be and should be understood in its symbolic function as a broadcast or messaging machine for inviting the world to join the struggle in favor of the modern liberal democratic ideal of national polity and international relations.

Simply put, the UN, and by extension, the UNFCCC, is an ongoing, continuous, spectacular public sphere drama of the Enlightenment liberal political ideal.

Following Jacques Derrida, we can see the whole UN process as what he called a philosopheme.

To quote Derrida at length from Ethics, Institutions, and the Right to Philosophy (2002, p.3):

“These [UN] institutions are already philosophemes, as is the idea of international law or rights that they attempt to put into operation. They are philosophical acts and archives, philosophical productions and products, not only because the concepts which legitimate them have an assignable philosophical history and therefore a philosophical history which is inscribed in UNESCO’s charter or constitution but also, by the same token and for that very reason, because such institutions imply sharing a culture and a philosophical language. And from that moment on, they are committed to make possible the access to this language and culture, first and foremost by means of education. All the States that adhere to the charters of these international institutions commit themselves, in principle and philosophically, to recognize and put into operation in an effective way something like philosophy and a certain philosophy of rights and law, the rights of man, universal history, etc. The signature of these charters is a philosophical act which makes a commitment to philosophy in a philosophical way. From that moment on, whether they say so or not, know it or not, or conduct themselves consequently or not, these States and these peoples contract a philosophical commitment by dint of joining these charters or participating in these institutions. Therefore, these States contract at the very least a commitment to provide the philosophical culture or education that is required for understanding and putting into operation these commitments made to the international institutions, which are, I repeat, philosophical in essence.”

So the UN itself, and by extension its subsidiary UNFCCC, are philosophemes—and what is the culture that they share? What is the philosophical language/cultural content that legitimates them and makes them what they are?

Let’s not avoid the problem. Let’s name that philosophy and expose ourselves. We are talking about the prescriptive, performative Constitutional language constitutive of the nested, relatively autonomous institutional domains that define our modern western societies: free market/capitalist economic spheres, free speech public spheres, and checked and balanced democratic political spheres (three equal branches of government).

In what follows, it will be necessary to recall that the UN (and all of the modern constitutional democracies) were founded on a mishmash of both libertarian and distributive principles of justice—both liberty and equality are institutionalized in policy processes that amount to contestation of what these terms can and should mean.

Yes, liberty! But liberty as private enterprise and private property without social and environmental limits? or liberty as freedom to enjoy the social and environmental commons and effectively join in the collective political determination of their fate?

We are talking about the contested culture (language/system) of European Enlightenment expressed and embodied in the constituent institutions defined by modern liberal political science!—a language/culture system that we discover to be already up and running when we arrive here to begin our analysis of UN climate negotiations at 21st Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change(COP 21).

Propounding that culture (system) and expanding it is the self-styled UN mandate.

And all of this is now being applied to the question of the planetary environment and the great 21st century challenge of climate change and the energy transformation that it requires of us.

The current reference is to climate change, but the actual arena is much broader—it is the whole question of planetary ecology that hangs in the balance, and this is made obvious by who in fact actually responds to the UN invitation, namely the whole global environmental movement, from its establishment elements to its most militant self-appointed advance guards in the non-violent direct action movements that spring up everywhere across the horizon of globalization under the banners for example of the Sea Shepherds, Green Peace, Friends of the Earth International, Earth First! and the Earth Liberation Front in Europe and the US, as well as myriad other incarnations of the equivalent sentiments that attach themselves to local environmental conflicts everywhere. Consider in this regard the Cochabamba movement—and the considerable impact of its World Peoples Conference on Climate Change and the Rights of Mother Earth, which produced the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth.

I am using the term modern here in a way that needs to be specified, in order to avoid misunderstanding.

What does it mean to be modern? Among other things, it means to adopt an attitude of continual improvement; constant self-reflection; self-assessment; measurement; and all of this in and through the continuous application of science to development ad infinitum, especially economic development, but also self-development. Self-expansion to infinity. Growth as the supreme value propounded by institutional modernity. In other words, being modern means remaining an open and unfinished product. What is modern is still open, not yet fully determined. Change is the expectation and the desideratum, as opposed to the traditionalist seeking of (eternal) return of the same.

What else designates the modern? Universalism. Universal human rights, for example, and ultimately the drive to conceive and materialize them in juridical institutions for self-government through consent.

Consider the UN Declaration of Human Rights (pdf) in this context. How does it begin? What is it about? What values does it propose to institute in and propound by way of the UN and its subsidiary organizations, including the UNFCCC?

“Article 21. 1. Everyone has the right to take part in the government of his country, directly or through freely chosen representatives. 2. Everyone has the right to equal access to public service in his country. 3. The will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of the government; this will shall be expressed in periodic and genuine elections which shall be by universal and equal suffrage and shall be held by secret vote of by equivalent free voting procedures.

Let’s begin with Article 1: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in the spirit of brotherhood.”

That is indeed a philosophical statement. Ontological, to be precise: a description of the individual thinking thing, the subject (of social action, to be precise; the agent).

And all of this in terms of dignity and rights; reason and conscience; modern ethics and science; and especially in terms of psychology—for it is all couched in psychological terms describing the mechanisms of obligation. It says that human beings all have, by conscience, a duty to be what we are, modern, and thus to embody and enact the dignity and rights laid out for us first of all by nature, which is after all the mysterious origin of our bio-psycho-physical apparatus (see especially The Federalist Papers in this regard), and second of all by the whole line up of state constitutions, at the end of which we find the Universal Declaration and the UN Charter.

These latter thus stand in the present at the leading edge of cultural artifacts and practices that are emerging from the deep historical transformation of European intellectual and political history of natural rights.

As a side note, for an application of this same perspective on natural rights discourse to the US national social imaginary and its local instantiation in the redwood region, which I describe as the cultural engine of California’s redwood timber wars, see my Trouble in the Forest: California’s Redwood Timber Wards (University of Minnesota Press 2009—throughout, but especially the Introduction).

What does all of this has to do with ethnography and the politics of climate activism?

Ethnography begins and ends in theory. The theory or idea you have of the object you are studying, and which thus guides you in the organization and design of your research program, will have to be revised and extended if your research has been successful—because, don’t you want to learn something new? Are you not asking questions that put the whole edifice of your ideas at risk?

What I am describing here is the theoretical grounds and justification for the research John Foran and I are embarked upon in in 2010, when we began our collaboration on what I call the international climate wars.

We are conducting a global ethnography of the entire field of social struggle that constitutes the climate wars as such, with a special focus on the global climate justice movement, which is actually a movement for climate governance and against unfettered capitalist-driven climate change. Because the movement takes the UNFCCC as a principal object of criticism, hounding the people who preside over it and those who seek to capture its power for divergent ends, to study one is to study the other—and so to study the climate wars is to study the negotiations, the movements, the states, the markets, the corporations, globalization and the UN as they operate together in a cultural system.

Global ethnography, as I use the term and develop the method, is essentially a method for global studies. The object of study, broadly conceived, is globalization in general. But, after everything we have been through in the last 30 years, and everything that we have read under the sign of this colossal term—globalization—and everything we have already said and written about globalization, as individuals and as scholars or activists—we should pause for a minute to reorient ourselves with a couple of excellent definitions of globalization, words to which I have so often appealed that I now claim them as my own, allowing for the fact that no definition can possibly be adequate. They come from former UN Secretary General (1992 -1996) Butros Butros-Ghali and from Teresa Brennan’s extraordinary book Globalization and its Terrors (Routledge, 2003):

By the term globalization, I mean, with Butros-Ghali “the growing interaction and interdependence of all the nation-states in every way—including all political, economic, and social phenomena.”

Thus, globalization is understood as the multiplication of exchanges and information.

And with Teresa Brennan we should add that “Globalization is the continuous and logical outcome of the process of extension, a process which begins with the division between household and workplace, grows through specialization in production, then through colonialism, concentrations in land use, through urbanization and suburbanization, and other forms of spatial reach” (p.3).

I have a special affinity for Brennan’s terse formulation because of the notion of division that lies at its dynamic core; it finds division at the foundation of expansion in space. By dividing work from home and stepping away from what is local to profit at a distance, space is substituted for the time of the natural reproduction of nature and labor at home. Instead of taking the time required to wait for land and labor to regenerate at home, the search for profit expands in space, speeding up the accumulation process.

In Trouble in the Forest I place the appropriation of native lands in Humboldt at the origin of redwood commodity circuits. The institution of redwood capital in Humboldt begins with that division—a division from which the losses associated must be noted as unrectified injustice as well as unpaid cost.

Thus, the history of the extension of the world economic (culture) system in time and space is the history of the externalization of costs onto communities of environment and labor and over the previous owners or occupiers of that space, and so it is at the same time the history of the production and accumulation of grievances directed at those accumulations of wealth and power. That is why global ethnographers should study place-based conflicts, so that their object will include both domination and the resistance it generates and which it thus contains within itself.

It is easy to see how these definitions of globalization shape the design of ethnographic research—or rather how they should shape research—by leading us into the radical critique of capitalism (whereby radical I mean simply a perspective that includes the possibility of non-market solutions to the market failures of globalization).

In today’s world, to address the facts in rigorous, consistent, single case studies of what the arrival of the globalizing modern world economic (culture) system of capitalism means in every new place into which it extends itself is to be radicalized.

The term globalization indicates the place-making expansion, indeed the universalization, of that world economic system, which is making places like the north coast redwood region of California into places of environmental conflict—places of converging indigenous, labor and environmental movements.

This way of thinking forces us to focus on the system of alienation (separation/division) for private accumulation that profits, as you can see, by externalizing costs on people, on communities of labor, and on nature—that is, by not paying full price, which is the same as making everyone else pay, or separating/dividing/alienating them from what is rightfully theirs (in the case of labor), and extraction from nature (beyond its carrying capacity/its capacity for reproduction).

Of course, climate activism will and must prove to focus on the same. Producers of greenhouse gasses are not paying full price for the energy inputs into their productive processes. Rather, those who suffer from the effects of global warming are paying the price. Those who will suffer in the future for the historic accumulation of green house gasses will be paying an externalized and deferred cost for the rise of the industrial modern system of economic production. And they will pay that debt in blood and sweat.

Climate politics could already be seen moving towards this type of radical critique after the insurgence of neoliberal ideology at COP 16 in Cancun, at which the backers of so-called market solutions like carbon trading and UN Reducing Emissions from forest Destruction and Degradation (REDD+) came out in full force, only to meet stiff resistance and a preponderance of evidence that carbon markets are failing, with prices crashing and a measurable absence of incentives for transition to renewables, in part because new patently bogus credits have consistently proliferated, driving down the price of carbon to irrelevance.

But here I am getting ahead of myself.

I will thus postpone the evidentiary phase of the trial until the argument is fully laid out.

If my definition of globalization stands, then the emergence of the international climate change negotiations and the counter-public social forces of the global climate justice movement are expressing the globalization of…. Well? Of what?

I claim these phenomena embody and express the globalization of a perpetual public sphere struggle over property rights that had previously come to define the effects of the modern social imaginary on the local, regional and national scales.

That is the conclusion I reached concerning the struggle to save ancient redwood groves in northern California from a capitalist with a lot of junk bond leverage back in the days of financial deregulation under Reagan in the 1980s.

In that book, I explain how California’s redwood timber wars embodied the transformations of globalization, as those changes entered into the place of the redwood forest, which itself had been colonized by the specifically US national instantiation of the modern social imaginary.

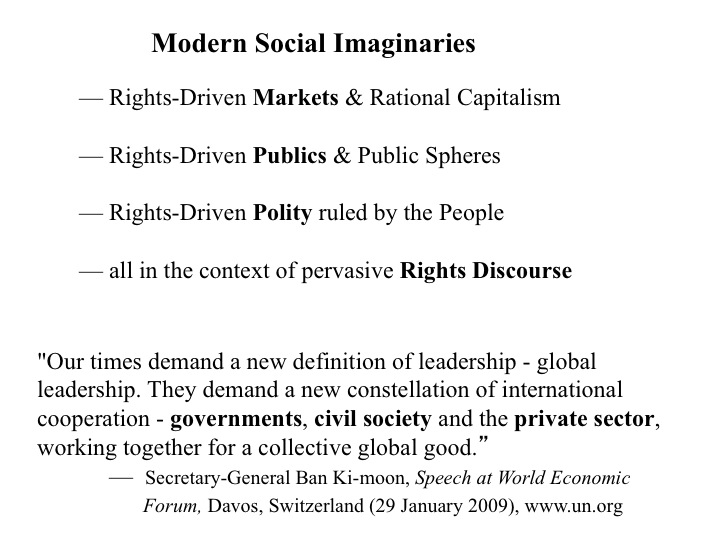

The concept of modern social imaginaries, which I adapt from various scholars including Charles Taylor, Craig Calhoun, and Michael Warner (Public Culture Public Culture 14, 1), amounts to a cultural theory of how these three central institutional spheres of modern, western, euro-anglo-american societies constitute the essential dynamism of these societies.

Rights-driven scientific capitalism and democratic republican polities, instituted constitutionally as relatively autonomous spheres of action, and designed to check and balance each other in a system of popular self-governance that protects minority rights while enfranchising the masses—that is the modern social imaginary. That is the society that we are born into and learn unconsciously, like a kind of mother tongue, a first language, the grammar or law of which we tend to forget; that is the modern social imaginary; that is the cultural unconscious of the western modernities.

And that is what I discovered objectified, or rather instantiated, in the redwood forest—where I found it driving a perpetual public sphere struggle over property rights.

I have to simplify here, but in the societies I am talking about, defined by these institutions and driven by the various rights associated with each relatively autonomous sphere, over time the sphere defined by property rights has tended to gain the advantage.

When exercised, property rights tend to accumulate as economic power, which is useful in penetrating and colonizing the other spheres (which are supposed to maintain their relative and checked and balanced autonomy). Economic power, the power of capital over labor, tends to accumulate as more power over labor for more alienation of more value, resulting in ever more power over labor for ever more accumulation, and finally a surplus of power that can be used as well over media, and thus public opinion, and therefore for power over government and thus legislation. This is of course what Habermas meant in the title of his 1964 book, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere.

Whereas the exercise of free speech and assembly tends to accumulate as public culture, and the exercise of political rights tends to accumulate as legislation, property rights tend to accumulate as surplus power over labor and thus over polity and finally over public culture.

The Upshot: Capital accumulation tends to colonize the entire lifeworld.

This may sound like a bunch of theoretical jargon, but to me it is a simple historical description of how modern social imaginaries swept across north America, for example, and colonized the redwood region in successive waves of Indian wars, labor wars, and finally the timber wars. This produced an historical record of perpetual public sphere discourse and struggle over the exercise and political regulation first of property in indigenous lands, then of property in labor and ownership of the values its blasts out of nature into commodity circuits, and finally of property in nature, in environment, and all of the relations between land and labor that sustain productivity and wealth.

And now this institutional dynamo is deep in the process of globalization. And the global governing institutions dominated by the western democratic nations and modeled on their constitutional set-up of a self-governing polity comprised of an executive branch, a legislative branch, and a juridical branch: the Security Council, the General Assembly, and the International Court of Justice, and of course the Charter, meant to embody and express and universalize the rights outlined in the Declaration, are set up to support institutions of free public culture and property rights-driven markets on a global scale.

The UNFCCC and COP 21 embody and express this as a perpetual global public sphere struggle over property rights.

In other words, if I am on the right track in treating UN institutions as philosophemes inscribed with the ideas and thus the ideal of modern liberal enlightenment science and ethics and political theory, there is a deceptively simple reason for this: economy and society and culture and politics are not neatly separable, regardless of what the various national constitutions and global UN charters say and do. When you make laws governing politics there are market consequences (the reverse is also true, market dynamism produces political effects or correlate dynamisms). And this is because the various relatively autonomous spheres are in fact mutually constitutive.

With these ideas guiding us in designing our research program on the Global Climate Justice Movement, the next step is to ask, What should we be looking for at COP 21 and beyond? What questions does the perspective outlined here generate?

First, What is the Global Climate Justice Movement? Where is it? We know it is out there right now, but where? Seriously, if you want to find something and investigate it, you must know where it is and start looking for it there. It is out there in the public sphere making public claims in a public space. But this is the new public sphere, not just the old town square and coffee houses, not just the newspapers, but these as well as all of the new cyber-spaces and -geographies of emergent global civil society.

Public claims in the new public sphere? OK, but claims about what? About global warming, of course, and how the rich who dominate and the people who supposedly represent folks politically are failing. We’re in danger!” they say, “The planet is heating up!”, they say, and then “Look at the science!” and finally “Somebody has got to do something!”

These claims are largely directed at the UNFCCC international climate negotiating events: you are not democratic enough; not open enough; not representative enough; not transparent enough; and too, too much under the influence of capital (Michael K. Dorsey 2011).

That is why the emissions reductions targets are set too low, they say, because targets in accord with the science and the drive to keep temperature rise associated with emissions to 1.5 – 2 degrees Celsius would be way too expensive. That is why the US has not signed the Kyoto Protocol; that is why the idea of profiting on the market mechanisms like cap and trade schemes and clean development mechanisms is making a mockery of the process.

Moneyed and vested interests with a lot to loose are distorting the process by which the international institutional apparatus is supposed to collectivize the will of the people and express that will in rational self-governance, which would of course be oriented toward collective self-preservation, not suicide!

In this regard we can cite the 2010 Greenpeace report on the Koch brothers, and draw attention to the well known US congressional refusal to legislate regulation of CO2, largely due to resistance by GOP members known to be cozy to oil, gas and coal interests.

For a definitive early investigation of this dynamic, see Naome Oreskes and Conway (2011) book Merchants of Doubt, and Robert Kenner’s 2015 film by the same name.

Capture by the fossil fuel lobby, in particular, and by corporate interests more generally, has thus become of the basic messages the movement is distilling and transmitting very clearly, and we can take it as a sign that at least some elements of the movement are rightly theorized, at least to some extent.

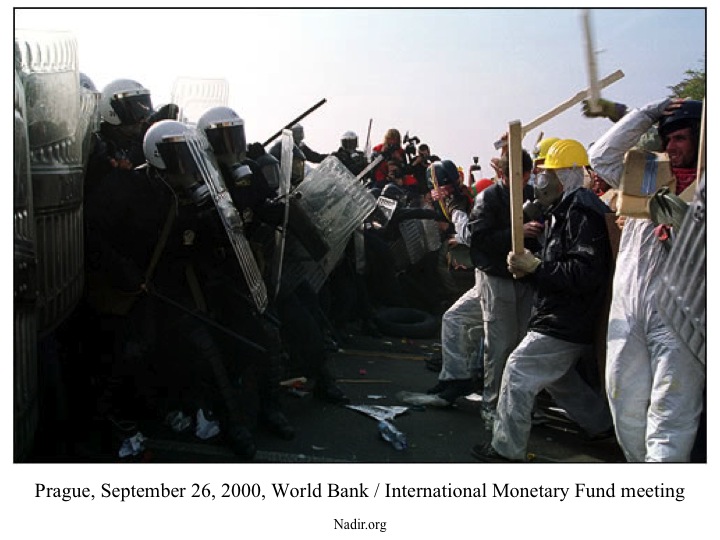

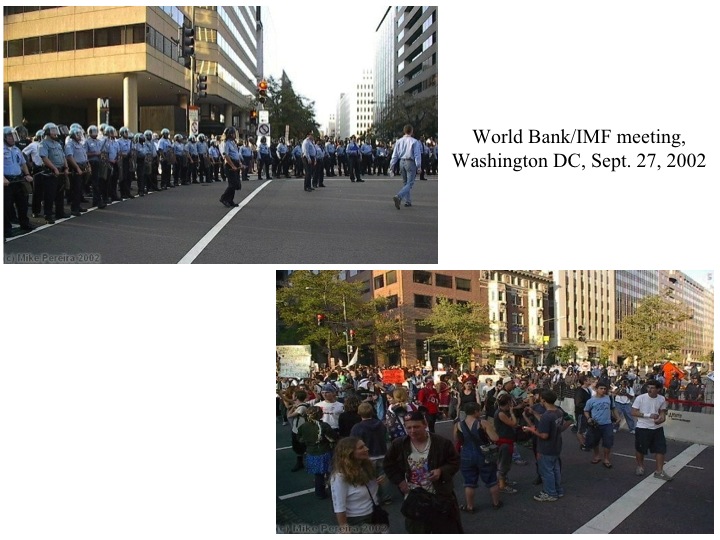

That sounds a little bit like the criticism that the anti- or alter-globalization movement developed over and against the WTO/IMF/WB troika, from the Zapatista revolt against NAFTA in 1994 through Seattle 1999 and the whole last decade of protest.

All told, the Climate Justice Movement’s response to the self-presentation of the UN in the climate process adds up to this: you need to live up to your promises! Your structure and charter promise universal human rights and rational, ethical, scientific mechanisms of self-governance, but the results are deformed by capital.

Therefore, capital must be made to submit before the law that expresses the will of the people, as that will is freely formed in public discussion.

It is a demand for submission to the rule of law.

That is the central proposition of the movement, as far as I can tell. And when you start reading the blogs and the websites and the demands of the climate activists, this demand is expressed as opposition to the prevalence of market mechanisms for mitigation and adaptation within the whole international climate negotiation process.

The whole carbon trading idea therefore comes under attack by these forces, which in general all conspire to assert the following approach to tackling the climate crisis: set a cap on CO2, issue AAUs (assigned amount units), RMUS (removal units) ERUs (emission reduction units) and CERs (certified emission reduction units), then let polluters trade for the newly fungibnle right to pollute represented by these new securities (aka carbon credits).

As the critics see it: the original cap is first of all set too low, and the original apportionment represents an unfair gift to polluters, and fraudulent new credits proliferate endlessly, swamping demand and sinking the price. There is an over-production of credits; it is too easy to qualify projects and create new carbon credits to sell, etc.

Hence, emissions are still rising, and this is rightly seen as emissions trading market failure.

So again, to oversimplify dramatically—the basic problem climate activists see is capital. They see a struggle between capital and. what? who? Capital versus whom?

Not just environmentalists, not just labor, not just indigenous peoples and poor peoples everywhere, not just planetary ecological integrity… but all of these!

Now we should take a look at the trajectory of recent social movements and talk about the convergence of various social forces in the Global Climate Justice Movement.

This is kind of like starting to study the civil rights movement in 1954—there have been some big events, and the forces are gathering, but I believe what is to come will be unprecedented. The stakes are very high; the problem is getting worse; and the UNFCCC is not going away. The UNFCCC Conference of Parties will continue to function as a symbolic channel of psychical investment and people everywhere will continue to channel their attention into it as the seminal form and forum of global public culture, which I now believe to be an inevitable expression of the technological transformation of society.

The world is getting wired, and real-time planetary co-presence is already here. It will not be long before all the world’s available attention can be turned on a dime. And the UN may be flawed today, but it can be reformed and strengthened, and I see climate change as a big challenge that it must rise up to and meet.

My personal hope is that it succeeds, and that the UN becomes a fully legitimate, democratic arbiter of global peace and security as well as sustainability.

Right now it has not reached that lofty height; it is too much dominated by capital, and it is not working quickly enough to radically alter the influx of greenhouse gasses to the atmosphere.

The movement’s tendency is correct. The question is, can it be socialized and used to really politically regulate and transform the world economic system?

Right now I would say that the empire of capitalist globalization has the upper hand. But the process of world socialization is proceeding. The forces of production are developing fast. And environmental limits are approaching. It may not be pretty to watch, but the coming disasters are going to produce stronger global political structures or it is game over.

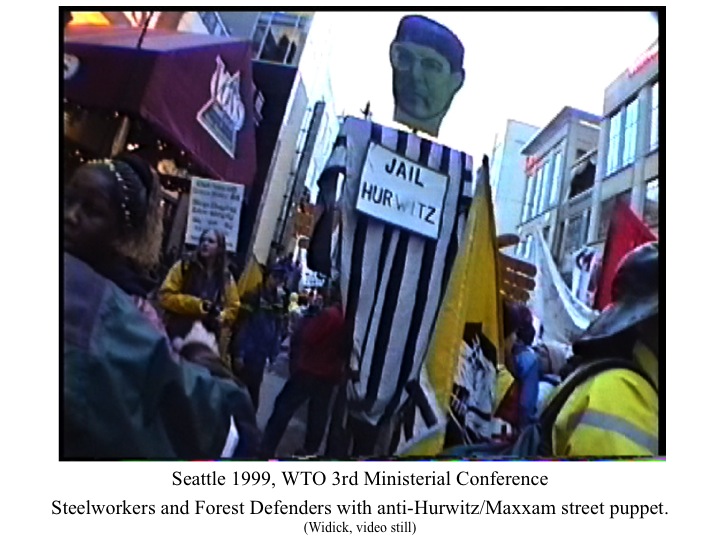

I was at the Battle of Seattle in 1999—that is where I took my first taste of these global, event centered convergences of social movements.

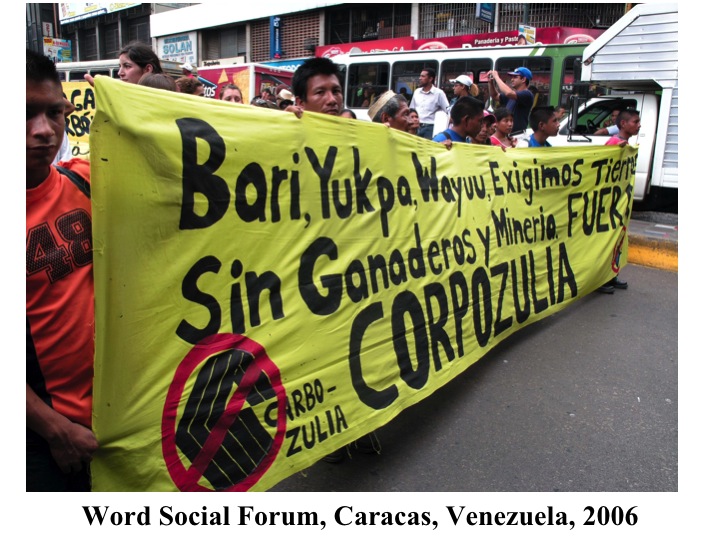

There is a palpable sense of debt and obligation to the Zapatistas and beyond them to the great indigenous movements of the global south, most visibly Via Campesina and the Movimiento Sem Terra. Their influence was felt at the IMF/WB protests that followed, too, and it remains prevalent at the World Social Forums convened in South America.

I was at Porto Alegre 2005 and Caracas 2006, and let me report anecdotally that the effect of these peoples’ movements was and remains profound. When indigenous and poor peoples and peasant peoples of the global south appear in the urban centers at today’s political counter-summits and social forums, they command great respect from their audiences. They are a rising force, and across the Bolivarian front their influence is huge. It should be and I hope it will be a growing force in the US, as it already is, more so, in Canada, where for example indigenous peoples and corporations are finding a strong voice in opposition to the grotesque development od the Canadian tar sands.

Here are some images I have collected which illustrate this convergence of social forces.

This is a video still I shot and published in my book on the redwood timber wars, it shows forest defenders marching together with United Steel Workers in Seattle 1999.

This Jail Hurwitz” puppet depicts the CEO of Maxxam, who bought the last 1% of uncut, unprotected ancient redwoods and said outright “I am going to cut them all.” He famously said—“This is America, we have property rights,” and “He who has the gold rules!” His actions and words sparked a social movement, or rather consolidated a number of latent social forces into a coherent movement with a villain as an object to confront. The Save Headwaters campaign ensued, and quickly moved beyond its defense of that singular grove into a general forest defense movement with demands to revolutionize the whole process of forestry and landownership in the region.

Hurwitz brought the steel workers into contact directly with forest defenders when he locked out the union at his aluminum factories and shipped in laid off timber workers as scabs. Steel workers sent emissaries to the redwoods, and the Alliance for Sustainable Jobs and the Environment was created by a coalition of forest defenders and union folk.

In that sense, Hurwitz did a great service for the convergence of labor and environmental movements at Seattle.

What followed over the next three years was a series of protests that constituted a real crisis for the WTO/IMF/WB troika and the ascendant neoliberal ideology referred to by many as the Washington Consensus, for which these institutions have generally been understood to serve as task masters.

Remember, that was the era of structural adjustment focused on the global south, a seemingly distant concern now that it is our turn in the global north to face the same harsh discipline of bank-driven austerity policies.

These images of the anti-capitalist alter globalization are part of a classic and mythical protest genre.

Notice the classic symbol of the taped mouth here at Cancun. It means “you are breaking your promise about the open society of transparent, representative democracy—we feel silenced!”

It now seems clear that the war on Iraq in 2003 took the wind out of these protests—and personally I know this is true, because it happened to me—I had to oppose that war, and it took time and effort out of the other conflicts I was studying, even though they are closely linked. Those were really bad times.

But the movement carried on even though the war machinery essentially took the stage.

Meanwhile the World Social Forum carried on its work as well. I first went in 2005, then again in 2006, to Caracas, VZ.

Finally we arrive Copenhagen, where the now familiar scenes of globally coordinated protest against the global symbols of emergent but failing economic and environmental self-governance, trembling under the grip of capital, appear again, transformed, better educated and more highly trained, with more smart phones and lap tops, this time focused on the international climate negotiations as the next and latest global symbol around and against which to rally.

And here they are again at Cancun.

And here they are again at Cochabamba for the World’s People Conference.

And here is the call for all peoples to come to COP 17, put out by the self-proclaimed, voluntary civic organization the Civil Society Committee for COP 17, in Durban, South Africa, 2011—the UN Climate Conference at which the nations agreed to design the new treaty that will be adopted this year in Paris.

Now let’s take a moment and look at some various examples of websites assembled on the eve of COP 17 in Durban, at which the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action was agreed, thus formally launching work on what will become the Paris agreement later this year.

Judge for yourself how you think these images bear on the above discussion.

Conclusion

I conclude with a few forward-leaning remarks.

First, recall the above invocation of the psychological mechanism of conscience and its role in producing obligation, duty and guilt, which I see as inscribed in the UN Charter and thus as part of the cultural law or grammar within which the UN addresses the public, demanding a response—that is the address and the demand, that is the invitation that it presents to us, and with which it produces, at least to some extent, purposively or not, a public culture of bad and good conscience.

I claim that this psychological address might be our only hope because, with Foucault and now everybody else it seems we know that practical knowledge, knowledge that is put into practice, is always power/knowledge. We encounter it largely and most consequentially in the form of power/knowledge complexes, in other words the disciplines, the sciences, the professional knowledge cultures like economics, for example, with its ideas like ‘rational choice theory’ and the incentivizing of competition for programmatic growth and efficient distribution of goods—such power/knowledge complexes are policy relevant, actionable ideas, and with Marx we must always remember that once an idea has been seized by the masses, it becomes a material force.

The founding liberal speech that claimed all people are equal and in possession of reason, as it did for example in the US Constitution, in fact had and still has this performative effect; it is still reshaping the world and calling new forms of subjectivity into existence, some of which might be positively auto-poetic and affirmative, and other of which are definitely negative and counter-public oriented.

On whichever side you see yourself, one thing seems undeniable—the UN is a gigantic well-funded spectacle of continuous address using precisely these terms, and the counter-public climate justice movement is answering its call in like and thus understandable terms.

So, we need to treat the COP process in these terms, as another complex of techniques among an infinite series of modern techniques that is productive of new subjectivities and new forms of life.

In Trouble in the Forest I detailed how the US land system was created and used in a way that created a gendered and racialized class system in which the public domain was for 100 years of national productivity systematically sold off to white men only, excluding blacks and women and Indians and instituting a national modern social imaginary in which we still encounter today the massive concentration of economic wealth and power, and thus control of political systems and public spheres, in the hands of men, white men.

But that is not in contradiction to what I am saying—everywhere you see that racialized and gendered power starting, at least, to crack up.

And clearly the entire history of social movements in the US has played upon the gap between what the founding speech promised and what was and actually is being delivered.

And the bad conscience produced by that gap has been exposed and pursued by trade unions and African Americans and Indians and women and gays and lesbians. No, not all the way, not to the end, not to the complete fulfillment of the promise—for it is easy to see how institutional racism and sexism and compulsory heterosexuality are still here today.

But I think we must still focus on the broken promise and use it to produce public culture of regret for past and present bad conscience, in order to feed the collectivization of political will for system change—not climate change (as the movement slogan coming out of Copenhagen articulated its core sentiment).

This means that one has to come up from underneath and get over capital to gain the upper hand.

The carbon-industrial system has inertia, and we have to change it from within.

My claim is that what the telegraph and the newspaper systems of the 19th century did for the US national self-identification across the vast new world in the industrial age, the internet and the world wide web are now doing for the emergent global environmental, labor and indigenous self-identification across the horizon of globalization.

Think of the UNFCCC COP 21 in Paris, with its dramatic deliverance of the Paris Agreement, as just one in a series of public rituals dramatizing the potential of perceptual and emotional co-presence on a planetary scale, as the world’s peoples attentions and identificatory attachments are channeled through media spectacle of converging people, labor and environmental movements.

And remember that this historic agreement is just the beginning. The question of carbon self-abuse and even self-extermination is becoming and will be one of defining questions of this century, equivalent to or even greater than, if such a thing is possible, the nuclear question of the 20th century (which has not been transcended but subsumed or incorporated within the great question of carbon transformation).

If I am correct and Paris Agreement is another beginning and not the end of carbon negotiations and counter-public spectacles of convergent social movements/forces, then we need to focus explicitly on this concept of spectacle and delve into its pedagogical function.

And I mean pedagogical function in the strongest possible sense of that word, as people have spoken about Seattle 1999.

The truth about Seattle is less important than the pedagogical myth that it has become. Did it really launch the anti-globalization movement? Upend the World Trade Organization’s Doha round? Put an end to the Free Trade Agreement of the Americas?

Was it really all of that? (See Deborah James, Impasse: Are We Nearing the End of the Corporate Globalization Era?, for an relevant take on this question, with many insightful links and references).

Such things are being said, it is being cited as such, and so it has become a founding myth for the anti-capitalist/alter-globalization social forces — many of whom are channeling their psychical energies and attentions through the COP process and will definitely show up in Paris.

I am one of those people.

What this means—what the concept of the spectacle means for the analysis of the UNFCCC Conferences of the Parties; the Paris process; the international climate wars—is that the perpetual public sphere struggle over property described above is really a struggle over the mental environment.

That is the terrain on which the concept operates.

That is the work that is does for the global ethnographers, like myself, who are trying to get their bearings on a very complex object.

It dials the focus in on the social-psychological and symbolic registers of public culture and puts the tools of socio-psychoanalysis in our hands.

These are people we are talking about—individuals, everywhere in deep identification with nationally constituted institutions of power, of property, and of religion, among other things.

That is what climate activism is up against—people clinging to power and wealth with real, true love, and all of the delusions and resistances and disavowals and rationalizations and projections and acting out that love entails.

Power does not relinquish power without a powerful, collective demand… if you will allow me to adapt the words of Frederick Douglas for my own purposes here.

So it is a struggle, and I believe and hope that the cultural-theoretical and sociological themes I have highlighted here today can help in the coming encounters with COP 27, in Egypt 2022, and by extension the ongoing climate wars.

References

Brennan, Teresa. 2003. Globalization and its Terrors (London: Routledge)

Ciplet, David and Roberts, J. Timmons . 2017. “Climate Change and the Transition to Neoliberal Environmental Governance,” Global Environmental Change 46, 148-156.

Derrida, Jacques. 2002. Ethics, Institutions, and the Right to Philosophy (Oxford: Rowan and Littlefield).

Habermas, Jurgen. 1964. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere (MIT Press).